THE SPIT IN THEIR HANDS

by Tenzing Barshee

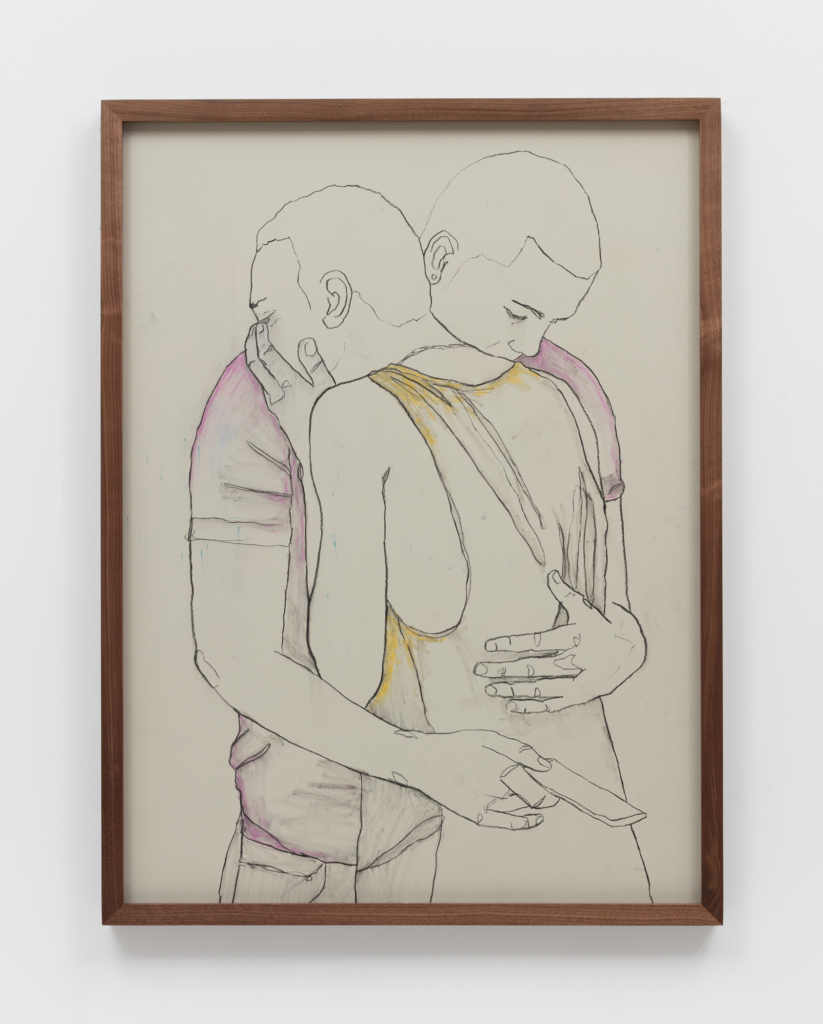

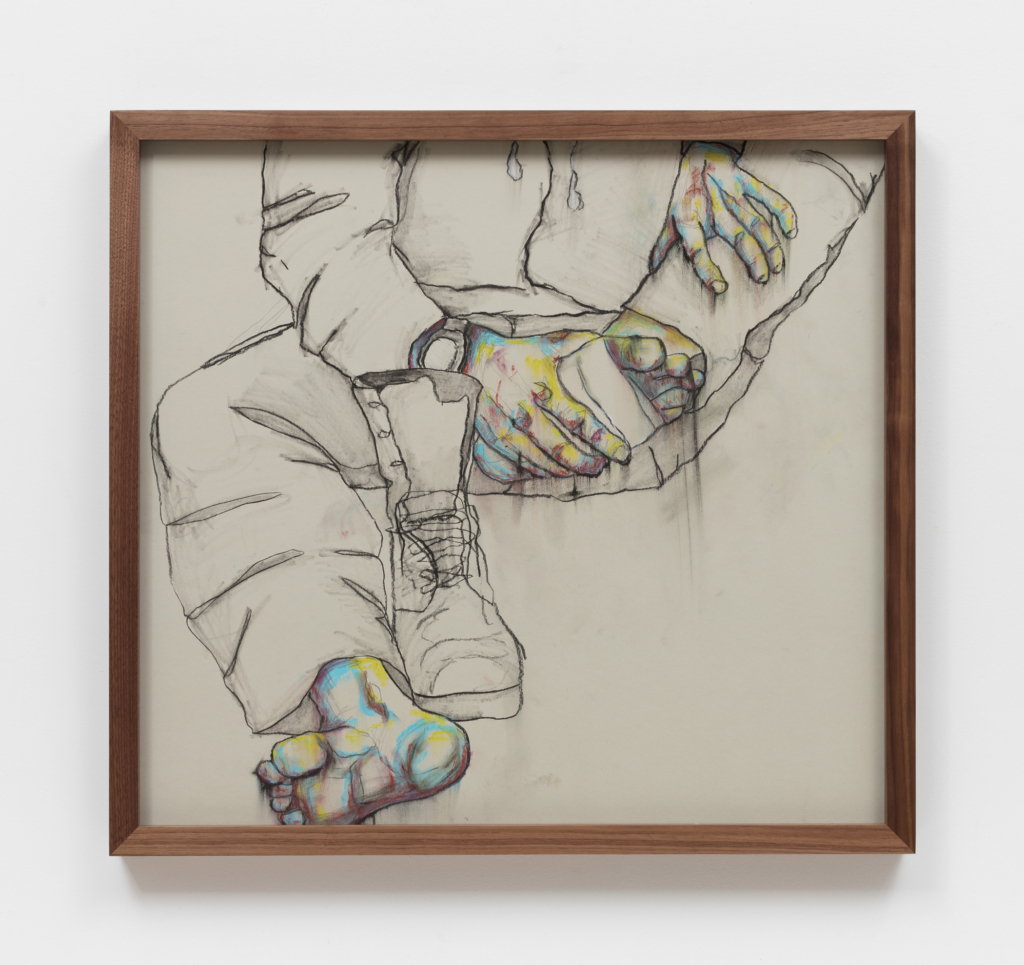

When Kyle Thurman draws figures, they appear like details of frieze-like scenes, framed close-ups; a short moment, a splash within a larger narrative. In a way, this lends his works a photographic quality—one instant, and as such, they bring to mind the heroes and their anti-parts of Leon Golub’s paintings. Like Golub, Thurman makes images that lack of references, such as a recognizable background; there is no information in regards to what surrounds these scenes. There is no context given: his figures are simply present.

Instead of the political intent that imbues Golub’s works, Thurman’s drawings are transcendent when it comes to being a mere instrument. In their tenderness, they suggest a different image of the body. To explicate this distinction, I draw comparison to Suely Rolnik’s analysis of the double capacity of our sense organs. The more dominant way of perception allows us to make sense of the world through its forms, onto which we project our representations, and ultimately, assign meaning to them. As such, this capacity is associated with time, the history of the subject and with language.

In the 1980s, Rolnik wrote about the “resonant body”. This relates to the second capacity of how we sensibly act in the world. Instead of simply performing as clearly outlined subjects and objects, maintaining a relationship of exteriority to each other, we have to consider “the body as a whole which has the power of resonating with the world.” She identifies this functioning as “historically repressed” and sees in it the potential to apprehend the world as “a field of forces that affect us and make themselves present in our bodies in the form of sensations.”

“The exercise of this capacity,” she writes, “is disengaged from the history of the subject and of language. With it, the other is a living presence composed of a malleable multiplicity of forces that pulse in our sensible texture, thus becoming a part of our very selves. Here the figures of subject and object dissolve, and with them, that which separates the body from the world.”

Blurring the lines and hierarchies between subject and object seems to be at the very core of Thurman’s project. To further illustrate this, we have to consider the matter of “decoration” in his work. Going back to the frieze-like appearance of his scenes —as if they were part of a decorative band— this enhances their function as elements of a larger structure or architecture. Which makes all the more sense, knowing that the artist thinks of his works as elements of a slowly forming graphic novel.

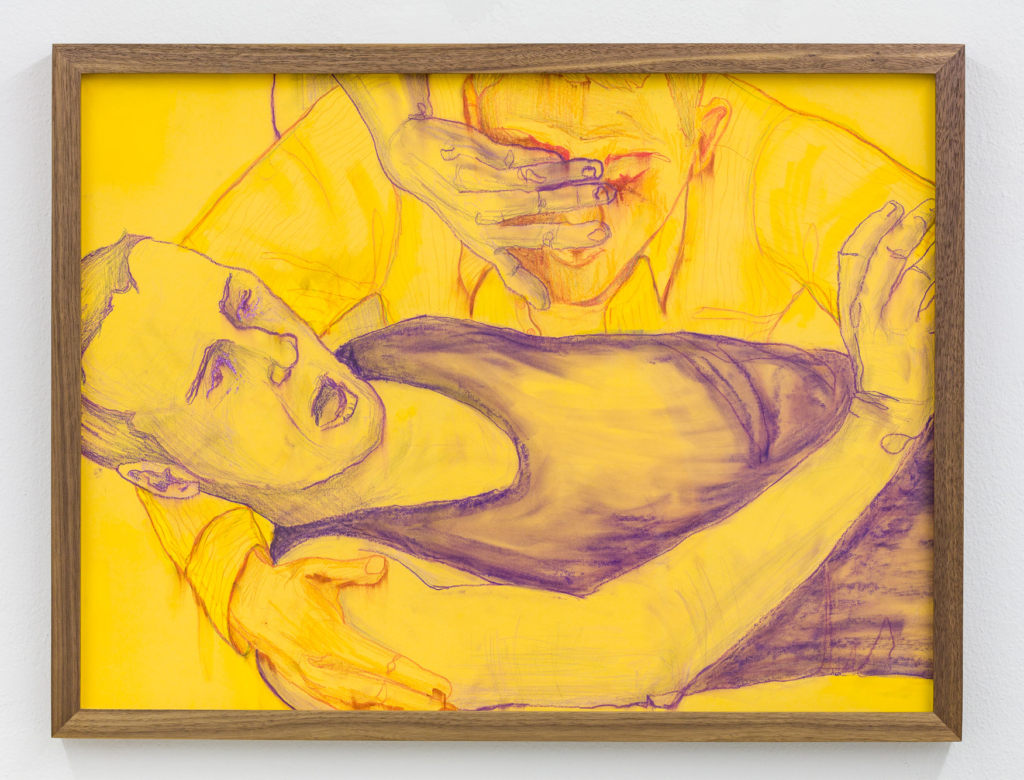

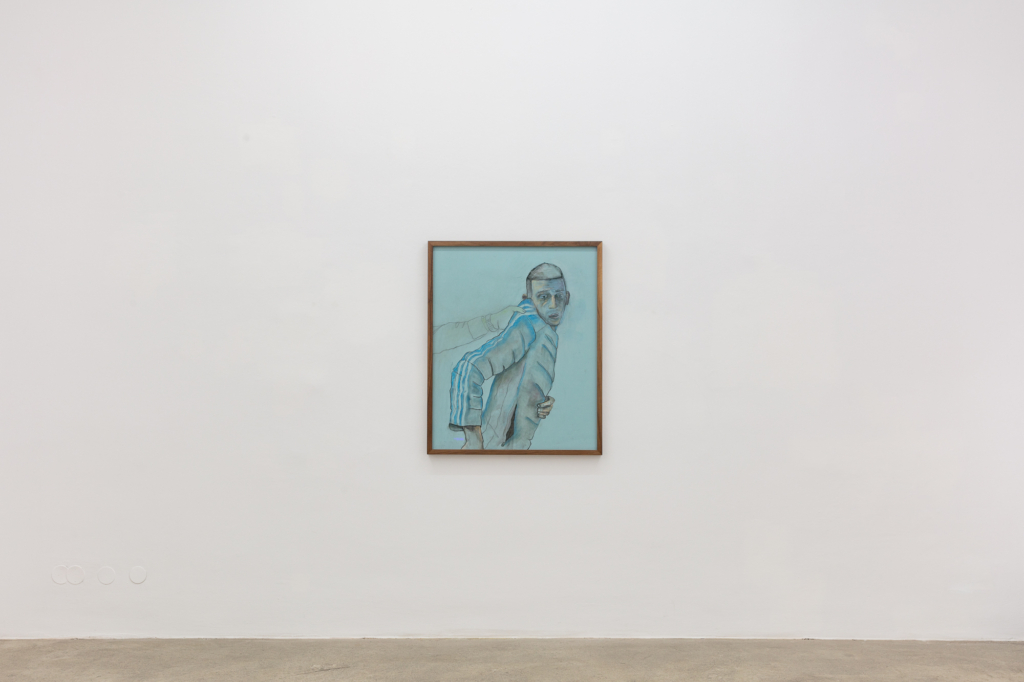

In different ways, Thurman ensembles his figures into a whole that has one or multiple embellished qualities. He accentuates parts of their bodies with color or glitter. Connecting them to something on a larger plane, a field or tempest of colours. Each of which behaves like a spot on a night vision camera, indicating the warmth of certain places, the temperature of emotive qualities. It might be obvious to relate the highlighting of body parts to how Egon Schiele coloured his figures. Then again, Thurman’s protagonists address youth and age differently, without exerting the pained expression, inherent to Schiele’s work.

In his essay “The Nature of Medieval Art”, Ananda K. Coomaraswamy counterposes our contemporary understanding of the word “decorative” with its older meaning. Today, he identifies, the word is pejorative. By applying the period eye, he finds that in medieval times it didn’t refer to “anything that could be added to an already finished product,” instead, it described the completion of anything “with whatever might be necessary to its functioning, whether with respect to the mind or the body: a sword, for example would ‘ornament’ a knight, as virtue ‘ornaments’ the soul or knowledge the mind. Perfection, rather than beauty, was the end in view.”

In the particular case, when Thurman applies glitter to the eyes of two wrestling men (Suggested Occupation 19, 2018), his intention is to embellish the scene in order “to almost tip it over the edge.” Like many of his works, the drawing allows for conflicting emotive states to surface. He speaks of “tension,” “violence”, “resistance” and “embrace,” all of which may act as key components of “intimacy”. The artist seeks out these contradictions. By adding a sparkle in the eyes of the wrestling men, he ever so slightly teases and queers the notion of masculinity.

The question what precisely is the ornament, aiding the construction of our image of masculinity—the manly decoration, pervades the work of Kyle Thurman. How do we think masculinity in late 2018? Although many of his figures are male and archetypal representations: soldiers, athletes, priests, the artist doesn’t merely invite to contemplate their gender, sexuality and psychology. Instead, he is driven by reflections on biography. He considers how his own body resonates in the world.

The men he employs often find themselves in a dialogical embrace. Touching, holding or otherwise interacting with one another. How do we embrace dialogue? Between eyes and objects, between bodies. One point of contact easily enables another. Again, the artist’s intent here isn’t simply to juxtapose his figures, but rather, and I’m going out on a limb here, to actually fuse them, to suggest their combined presence as something unified.

To talk of an instant, any image or photograph, means to talk about memory. Though, time reveals itself as a tricky component: the past, it seems, has the ability to speak fluently with its future. But then again, memory’s a bitch, we never know where its precision (or vagueness) is headed, it is so much connected to the affect that is attached to it.

For those who have been paying attention to the treatment of the figure and its expression, it seems pertinent to further address the matter of honesty: and the question of honesty begets the question of trust. By addressing the honesty of something, the problem of distrust is raised immediately. Any partial struggle for honesty must be brought back to its transcendent potential; everything is given its meaning by its forms, even when the real history reveals them for what they are—namely, lures, lures just like what any representational function ends up being, any relationship turns out to be.

Discussing trust means to confront betrayal. And here, we’re talking about colours. For various reasons, the reception of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s last film “Querelle” has called his usage of Jean Genet’s eponymous masterpiece a “betrayal” instead of an adaptation. For our purposes, we have to consider one of the film’s most striking aspects, which is held in its visual memory, its colours, the warm orange glow that suffuses the film and raises its temperatures.

Particularly, the drawing of the wrestling men, but also other instances where Thurman superimposes his figures atop coloured backgrounds, allude to the idea “of a raised (or lowered) temperature.” Kyle Thurman uses colours like elements of weather, and, as it doesn’t come as a surprise, the weather offers the most appropriate metaphors for intimacy. By clouding or lighting a corner or aspect of one his drawings, the artist plays with the intensities of intimacy that are implied in his work.

To reconnect the idea of “intimacy” to “decoration”, Genet’s writing itself offers insight. Referring to a passage from “The Thief’s Journal”, helps to further illustrate earlier reflections on the blurring of the lines of exteriority between different elements, the unification of two (or more) supposed opposites. Genet writes: “I did not see the spit in his hands: I recognized the puckering of the cheek and the tip of the tongue between his teeth. I again saw the boy rubbing his tough, black palms.”

There are a couple of reasons why people spit their hands. They could be performing manual labor, about to lift something heavy, or they spit to lubricate themselves to perform sexual penetration. While both instances of spitting serve a practical function, they also act as a sign, something is about to go down. It is exactly this bodily potential, which can be tracked in Thurman’s momentous depictions. There is another situation in which someone might lubricate their hands with spit: the most intimate handshake. To seal the deal, bodily juices exchanged, two people spit their hands before they shake on it, a ritual, possibly older than history.

“As he bent down to grab the handle,” Genet continues, “I noticed his crackled, but thick, leather belt. A belt of that kind could not be an ornament like the one that holds up the trousers of a man in fashion. By its material and thickness it was penetrated with the following function: holding up the most obvious sign of masculinity which, without the strap, would be nothing, would no longer contain, would no longer guard its manly treasure but would tumble down on the heels of a shackled male.”

Like Thurman, Genet evokes the decor of masculinity, treating his men with admiration, and at the same time, he is brutal.

“The earth cautiously turning,” Genet writes, “the Universe protecting so precious a burden, and I standing there, frightened at possessing the world and knowing I possessed it.”

Both reveal their figures unforgivingly, and even more than that, their lines and words suture them into tools of mere potentiality; the men of these fictions, they can always be both: lovers or murderers.

PRESS