the uncontrolled aspect of rushing into position brings together for the first time the performative-photographic practices of Sophie Thun (b. 1985) and Ulay (1943–2020). It also marks the first ever presentation of Ulay’s work in Vienna.

Sophie Thun and Ulay never met in person. (1) While Ulay was unlikely to have known about Sophie Thun, Thun was aware of Ulay’s existence. However, she never engaged with his work extensively. Given the proximity of form and content between both artistic practices, it seems as if they could have been in dialogue. Artists as lovers, artists as relatives, using a corresponding vocabulary, sometimes even a kindred grammar. (When we started working on this exhibition together with the Ulay Foundation, we joked that Ulay could have been Sophie’s grandfather.)

Solitary business

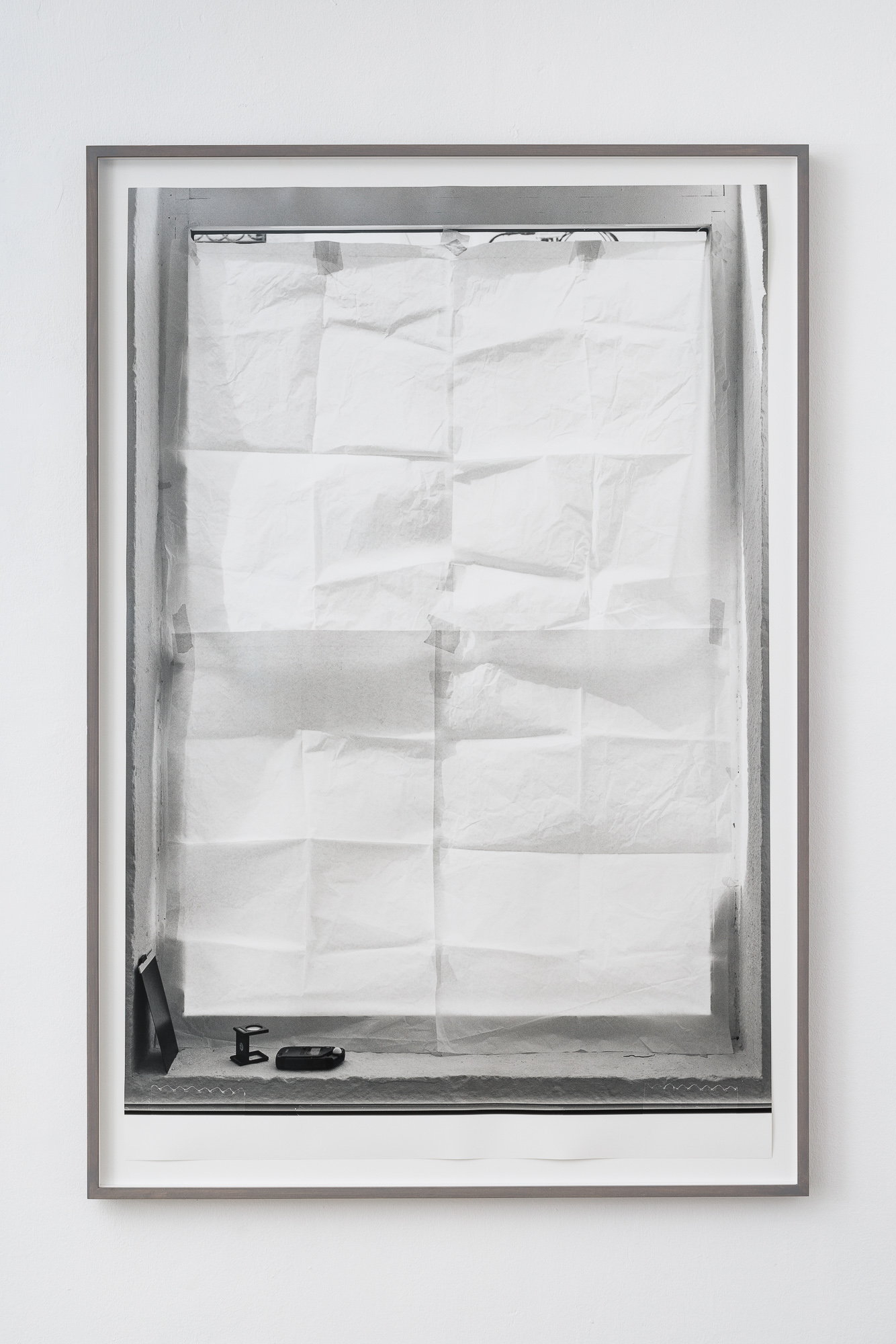

Sophie Thun uses the large-format wooden field camera (with either 8 x 10-inch or 4 x 5-inch negatives), utilising techniques of analogue photography, working with the chemistry inherent in the image-making process. Ulay, on the other hand, worked mainly with Polaroid, the so-called “instant photography” (the technique of the photogram as an artistic medium appears in his work at the beginning of the 1990s). If Polaroid arrests time, Thun’s photograms mark its passage; for an image to be revealed, extracted, mounted, and expressed, Thun, often surrounded by liquids, needs the action of light—and of time. Her working process is therefore slow, and she spends hours developing images in a darkroom; her photographs are chronicles of gradual actions. Thun also works extensively on-site, site-specifically, as part of her exhibitions. She activates the spaces so that they are in motion, simultaneously sites of image production, momentary archives, and points of contact with the public (in many of her recent projects, she has been present in the exhibition space for their entire duration). (2) This social aspect of her work, which is not merely an exhibition presentation but an essential part of her practice on location, brings forth a complementary contrast to the solitary image-making in the darkroom.

Ulay, as part of the commercial photographic laboratory he established in 1966 in Neuwied, spent two years in darkrooms, mastering all aspects of the analogue process (“Those were wet places!”). (3) After relocating to Amsterdam in 1968, he came in contact with Polaroid; it remained one of his central mediums throughout his oeuvre. In the 1970s, he worked with small-format Polaroid films (107, 108, and SX-70) and at the end of the 1980s moved to the larger Polaroid formats (the 20 x 24-inch camera and the biggest—the 40 x 80-inch camera), exploring the limits of the medium as well as other forms of (analogue) photography.

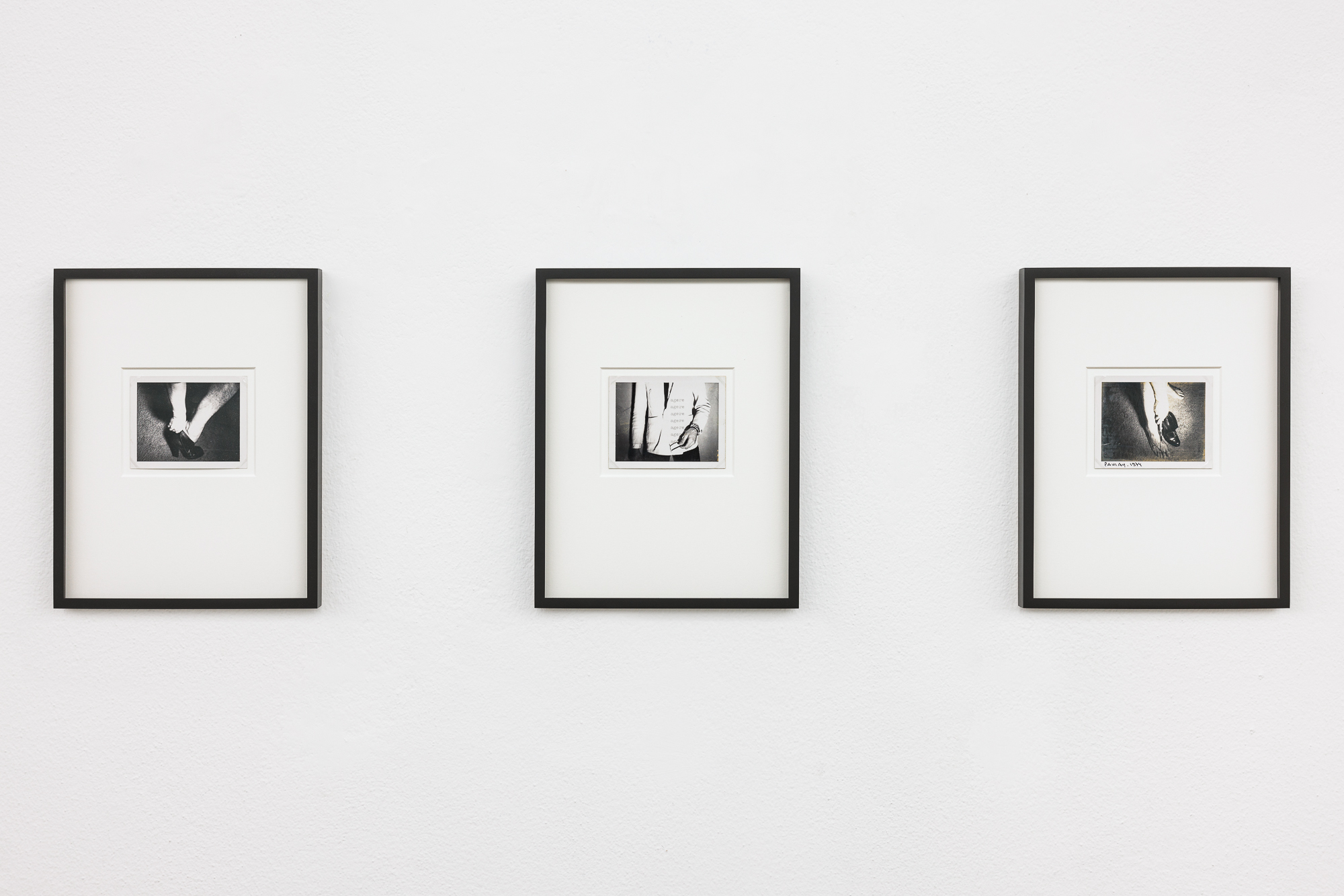

In the early 1970s, before he turned the camera on himself, Ulay was fascinated by what he called the “social nature” of the Polaroid camera, fostering a community around him. (4) Later, the joy of immediate image-becoming provided him with an extensive opportunity for intimate, profound self-exploration, culminating in hundreds of Polaroid self-portraits. In these fleeting, intimate performances without an audience, both indoors or outdoors, Ulay explored the foreignness in one own’s body, his masculine and feminine sides, and socially constructed issues of gender. He, an autodidact, so fond of the word “auto” (and all the connotations the word has [in German] in relation to self-determination, autonomy, and automatism), called them exclusively Auto-Polaroids.

In 2015, following her delicate photographic interventions in architectural settings, Sophie Thun turned the camera on herself for the first time. Since then—more extensively from 2017 onwards—the process of self-depiction has been an ongoing one. Regardless of her body position, Thun has consistently performed for the camera alone, maintaining a bold gaze and a firm grip on the shutter release (not as if possessing it, but possessing it, and with this act self-determining herself). Connected to the photographic apparatus, she is an extension of it; or rather, the apparatus is her prosthesis. Her body—like Ulay’s—is her vital tool.

The half

In German die Hälfte and in Dutch Helft, in English “a half” (noun) is “one of two equal parts of anything”. “Half” (adjective) means “consisting of two things in equal parts” or “not full or complete”. (5) Ulay’s fixation on the notion of the “half / halves” and “duality” (in German he uses the word Zweifalt, “zerspalten; in zwei Teile geteilt”) can be traced back to the late sixties, when the genesis of his subsequent works (the most well-known of which is probably the extensive series of S’he Polaroid transformations) was underway. Prior to Auto-Polaroids, Ulay used the word and visual poetry to approach the unstable states of in-betweenness. He referred to the short expressions that he wrote on his typewriter, first in German and later on partly in Dutch, “aphorisms”. (6)

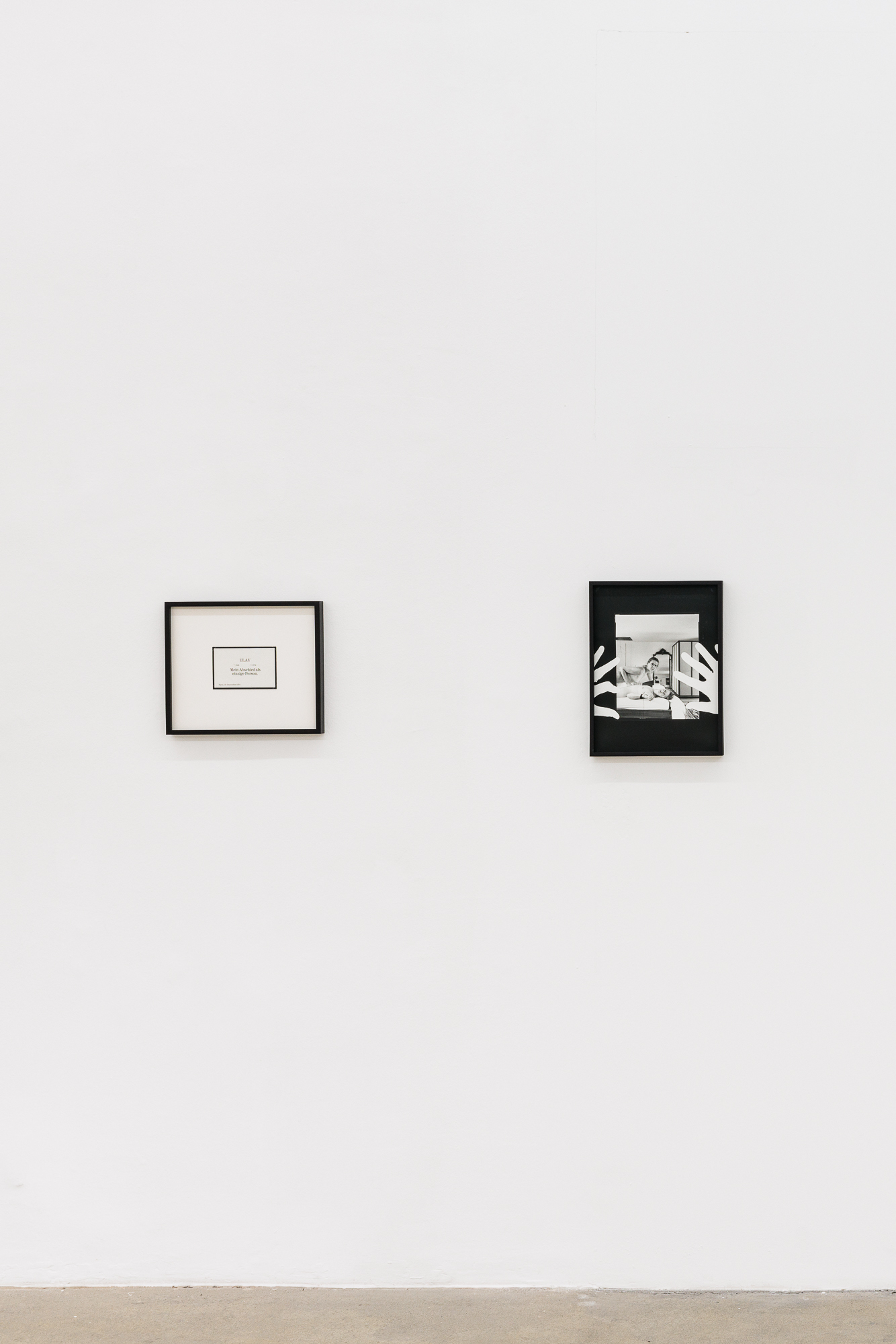

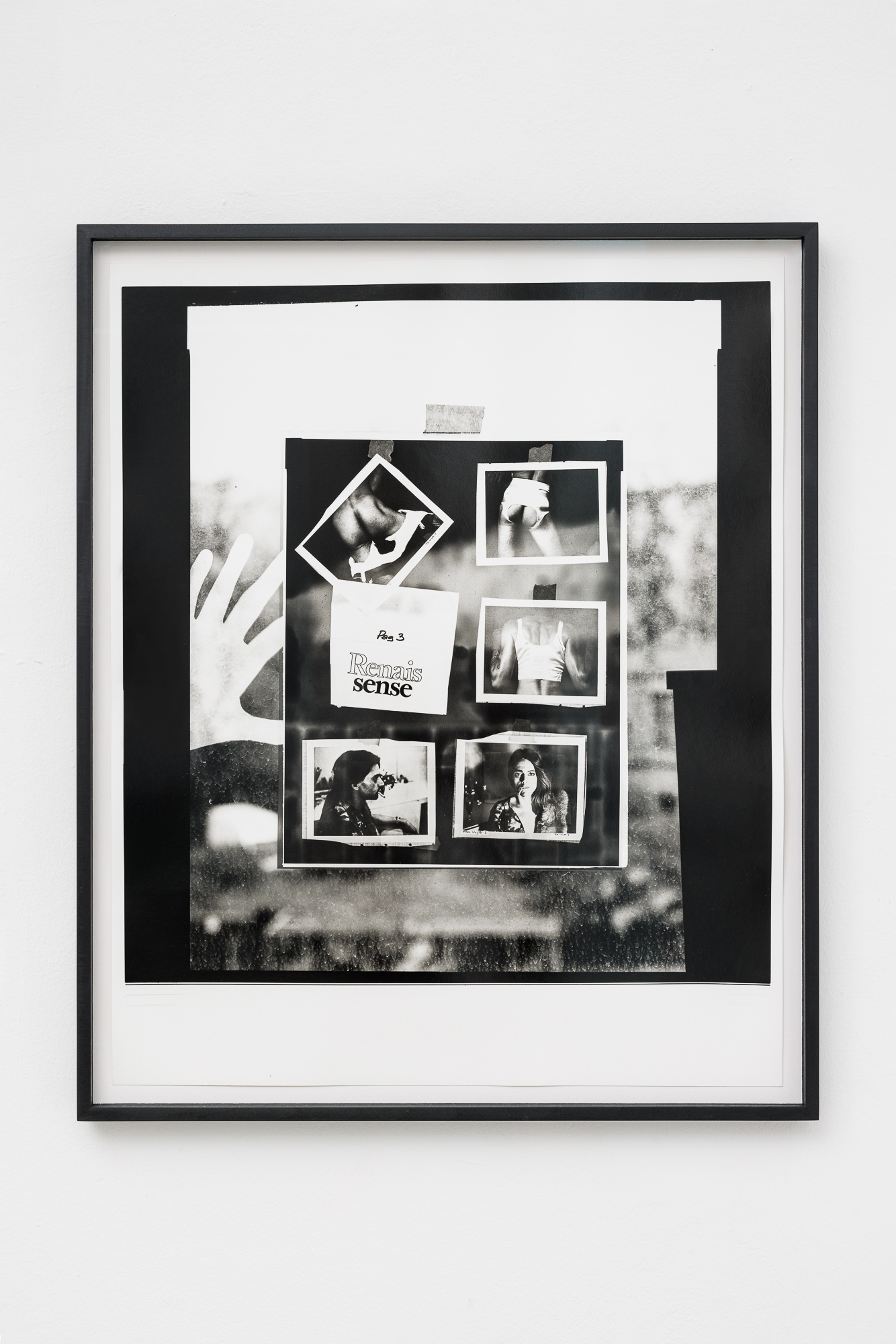

A series of Polaroid collages with typewritten aphorisms on their surface, Renais sense Aphorisms (1972–1975), in which Ulay combined Polaroid close-ups of various parts of his body with parts of other people’s bodies, presenting himself as an incoherent and discontinuous gendered being, resonates particularly with Thun’s method of cutting and collage. She cuts through the negatives with a cutter before exposure, then holds them together with her hands composing fragmented settings, highlighting the construction of photographic processes.

Seduction, eroticism, and auto-eroticism are important dynamics in both Thun’s and Ulay’s self-stagings. They both desire and perform their (own) acts of desire for the camera, which is a recurring protagonist in their self-depictions, especially in Thun’s work. Regarding the subject-object relationship (photographer-model), both artists embody the exhibitionist and the voyeur at once. While Thun seeks (sexual) encounter with herself, at the same time dominating and being dominated, Ulay attempts to unite his male and female traits (S’he). In some other works, which he signs with the amalgam Pa-Ula-y, he anticipates the communion of the pair that becomes one: a unity. Two individuals, two halves, fused into one being—not a state of one, but a state of two in symbiosis. When one (Paula) of the two leaves, this can lead to a total dissolution of the self; the personal suffering triggers in Ulay a desire to sever part of his foot, rescale it, to fit into Paula’s shoes (Bene Agere (In Her Shoes), 1974). The full potential of a symbiotic state is later materialised in the twelve-year relationship (1976–1988) with Marina Abramović. The clear symmetry between the male and female principle as part of their early artistic period, Relation works (1976–1981), leads to a birth of “a third existence that carries vital energy”, which Ulay/Abramović call “that self”. (7) Echoes of their relationship are in Unhurt (2015), a series of graphic prints made by Ulay as part of his late “pink period”. The starting point for Unhurt were the seminal photographic documentation of their various Relation works performances. (9) In their collaboration, Ulay was the one to position the camera, and with it, frame the gaze of what we today consider iconic images. The negative space between two bodies performing together—the in-between space of absence, the charged coexistence between the male and female principle—is now given form; the negative space becomes the leading character of Unhurt.

While there—at least visually—appears “one Ulay” (even if his face is cut in half) in each of his Auto-Polaroids, Thun, in her performative black-and-white self-stagings, captures the uncanny, impossible encounter of her fragmented selves; there are several Sophie Thuns in one photograph. Her fragmentation, replication, and multiplication of the self has less to do with a certain deep discomfort (in Ulay’s terms) with one’s body or the expression of emotions—even if her work stems from personal experience—than with our “ways of seeing”, her profound exploration of the limits of the photographic medium (through gradual processes, superimpositions, and the use of mise-en-abîme techniques, she also replicates space) and its ontology; the slippery identity between the real and the illusory, always already in the past. Does “to reproduce” mean to disappear and dissolve, or to be reborn, each time anew? Renais sense is the overarching name Ulay gave to his early body of work (1970–1975). This neologism refers partly to rebirth (renaissance) and partly to a kind of countersense, nonsense. All the physical transformations and multiplications lead Ulay to feel like Sisyphus—“it was senseless, useless” (10) —to the absolute depletion of himself (diptych Soliloquy (Shooting-Self), 1975). The idea of a total disintegration through multiplication (a certain auto-aggression sensed in both Thun’s and Ulay’s self-stagings) is connected with the exhaustion of the Self that can only stay on the (photographic) surface. With a death announcement in the form of a funeral postcard, Ulay bids farewell to himself as a singular person; a metaphorical act marking the end of the obsessive search for identity, announcing the symbiotic relationship with Abramović in art and life.

When I think about Thun’s and Ulay’s practices, I think about what happens when I, the word my medium of choice, repeat a word out loud so often that it loses its conventional meaning—does it become a murmured buzz or music? Thun’s and Ulay’s performative photographic works are executed with precision and care, but chance remains a defining element of both their practices. Slipping from control means letting chance—life—in. There is an “uncontrolled aspect of rushing into position” (11) just before you “shoot”. The liberating potential inherent in the unplanned and the unknown is particularly present in image-production; there is no way back, no chance of correction.

Skins

Both Ulay and Thun have developed not only an intimate and emotional but also a physical relationship with photography. It is as if they were enacting what Susan Sontag stated: “There is the surface. Now think—or rather feel, intuit—what is beyond it, what the reality must be like if it looks this way.” (12) In the genealogy of cutting and removing his skin—human skin and photographic film are both protective layers of the active chemical substance underneath—Ulay peeled off the protective outer layer of the Polaroid image (diptych Soliloquy, 1975). Looking directly into the camera, he, for the camera, removed an emulsion-like layer from his face and, shortly after, also from the Polaroid image—the Polaroid became a fragile artefact, so vulnerable (like the Self) that Ulay did not allow to exhibit or frame it until 2020, storing it in the darkest corner of his archive. (13) In Ulay’s storage, Thun takes photographs—a few months later, the small-format, Polaroid-sized work emerges (Skins, 2024).

Both artists have also worked extensively with the technique of photogram, a 1:1, life-size method based on physical contact. In the dark, they press their hands and bodies onto light-sensitive paper for the duration of the exposure; after the exposure, the sheets are developed, fixed, and rinsed. What we see are white silhouettes, traces of a bodily presence that is absent from the photographic image. In this way, Thun’s hands, by now her unmistakable feature, also hold, touch, frame, and carry Ulay’s presence in Ljubljana, Vienna, and Berlin (Negative to positive to negative to positive, Amsterdam to Resljeva to Vienna to Blücherstrasse, 2024).

In the 1990s, after the break with Abramović, Ulay experimented with a new technique he called “polagram”, a combination of a Polaroid and the classic photogram. Standing inside a life-size Polaroid camera (working inside Flusser’s black box), he created images by moving a beam of light with colour filters directly on the negative, relating to it with his own body in a 1:1 ratio—body and image, just like with Thun, coinciding. In the untitled polagram from 1993 that is on view, Ulay sketched four hands and a vessel onto the negative. A vessel as a substitute for a body, but also, for Ulay, “vase is a skin […] hollow within and hollow around”. (14) The vase is a recurring motif in Ulay’s work from the eighties onwards, a testament to his sustained interest in the notion of negative space (as the space between two or more objects or two or more bodies), which was central to his performances with Abramović. Negative space as a space of balance, a fragile in-between condition, also resonates with the bodily imprints Thun leaves in her photograms.

The archive

Over the past few years, Thun has created her own archive of images, mapping not only the various sites and architectures she has inhabited throughout her work and exhibitions, but also all the different gestures and positions of her own body, to which she continually returns, reusing them in new analogue photographic compositions. It seems that almost every one of her exhibitions contains at least part of the previous one—her performative-photographic work in general is in a constant process of revival and reconstruction.

Ulay’s life and work have been marked by a certain fleeing—running away from his origins (only to return to himself again and again) and, at a certain point, withdrawing from the art world. Iconicised and overshadowed by his relationship and collaboration with Marina Abramović, his solo work remains largely unknown and somewhat untheorised; “the most-known unknown artist”, as he liked to call himself, was an organised and precise conservator, a careful archiver of his own past. “I’m a hideaway artist. I have done so many things that people don’t know about—they can’t know because they don’t have access to my archive,” he stated in his last printed interview in 2019. (15) Ulay was comfortable alone, but he was also happy if people came looking (for him). With Sophie Tappeiner and Sophie Thun, we visited his storage in Amsterdam and in Ljubljana, entering the spaces he called home. The initial idea was to create a dialogue between the existing works of both artists. However, in an act of unplanned spontaneity, Thun also created new works. In the context of this exhibition and the posthumous engagement with a past artistic legacy, it seems essential to point out that the indirect, somewhat one-way exchange between Thun and Ulay is not a singularity in her practice, but rather an impulse that should be read as part of the ongoing, intimate, in-depth dialogues that Thun has already established with two other “archives”: that of Irène Codréano (1896–1985), a Romanian sculpture, and Zenta Dzividzinska (1944–2011), a Latvian photographer. In this respect, her art-making is also a way of building community through acts and gestures of care, through her active engagement with the hidden or marginalised histories of art. While addressing the ethical issues that underpin her revisiting of past narratives through a kind of appropriation, she builds kinships: be it with local spaces (whether Ljubljana or Riga), there-based institutions, where she spends weeks, sometimes months, with the people, hidden behind and in the archives, or with neglected artistic legacies per se. Her actions do not stay solely on the surface but have profound effects in the now.

Es regnete

Hana in bed (Vienna, 2024) awake, paralysed with anxiety, not sure how to start this text.

Ulay in bed (Ljubljana, 2019), the chemotherapy was a month ago, Hana sitting on the chair next to him. Ulay dictating the email, Hana’s fingers retracing his words on the keyboard. Lena cooking lunch. The three of us, working on one of his exhibition projects.

Ulay in a hotel bed (London, 2019), during an interview, says: “I have no fear.” (16)

Ulay was fearless. Or at least he tried to appear as such. How else could he have performed acts of self-harm, cut his skin, sew up his mouth, or steal what was said to be Hitler’s favourite painting from the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, only to relocate it to the apartment of a Turkish immigrant family living in Kreuzberg? He titled what was to become one of art history’s most seminal actions in public space Irritation – There is a Criminal Touch to Art (1975).

Sophie in bed (Vienna, 2021), motionless ((KJ MF MS AG FW LM AS EW) Portrait recropped, 2022). Her head tucked under the sheet, her hand clutching the shutter, a dark slide from her large-format camera in her other hand. “A place of destruction, of total depression, but also of pleasure, of sex and sleep,” she says. To be in bed is to be many selves; one of them is the self of attempted disappearance.

Sophie in bed (Vienna, 2022), with Sophie, both naked (Bei M+P im Schweinestall, 2023).

Sophie tells me a story that Daniel Spoerri told her about the inability to start working. It ends with the sentence “Es regnete,” which is also the first sentence of another, different story.

Es regnete (Kettenbrueckengasse 23, Daniel’s door, remember?), 2022, Thun’s camera reflected in the mirror that was placed on the door of Daniel Spoerri’s studio. The last photo before Spoerri moves out of his Vienna studio, the space where Thun, then without a fixed workplace, has produced most of her small-format photographic works in recent years.

After a long day, Sophie and Sophie T. and Hana in bed (Amsterdam, 2024).

Sometimes “there is no time left for fear,” says Sophie Thun about overcoming the doubts that accompany the beginnings (of her working process). (17) Lock the door, enter the sentence, rush into the position. Or, as Ulay would say: “If you must, you must”. (18)

—Hana Ostan Ožbolt

(1) Sophie Thun was born in 1985 in Frankfurt and grew up in Warsaw. She studied graphics at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow before moving to Vienna at the age of 22 to study painting at the Academy of Fine Arts. She came to photography “from a side”, the darkroom being the space at the academy where she could concentrate and detach from the collective painting studio spaces. Born Frank Uwe Laysiepen in 1943 in Solingen (then West Germany), Ulay studied mechanical engineering and in 1966 established a photographic colour printing lab in Neuwied, specialising in industrial photography. In 1968, at the age of 25, he moved to Amsterdam. From 1969 to 1971, he worked extensively as a consultant for Polaroid. In 1970, he enrolled in painting and graphic arts at Kölner Werkschulen in Cologne but left his studies soon after. He lived a nomadic life with a base in Amsterdam until 2010 when he found his home in Ljubljana. Ulay died in Ljubljana in 2020. In 2022, Thun made her first visit to Ljubljana where she began to work on her solo exhibition, which opened there in 2023.

(2) Here I mainly refer to Thun’s exhibitions at Secession in Vienna (2020), Kim? Contemporary Art Centre in Riga (2021), and Cukrarna in Ljubljana (2023).

(3) Ulay in Whispers: Ulay on Ulay (ed. Maria Rus Bojan, Astrid Vorstermans), Valiz, Amsterdam 2014, p. 84.

(4) Ibid, p. 124.

(5) Cambridge Dictionary, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english-dutch/half (accessed April 29, 2024).

(6) For example, two of Ulay’s aphorisms from the early 1970s read (formally, each word is on its own line, separated from the others): „Wenn ich nach draussen / draussen vor die Türe gehe / bin ich bang dass jemand gegen mich / durch mich / und ich in zwei Hälften / von oben bis unten / weiter läuft“ or

„seit dem Bewusstsein meiner späteren Zweifalt will ich rückwirkend bei meiner Geburt anfangend abrechen mit der Opalscheibe der infizierten Undurchsichtigkeit meine Väter Väter Verräter“

Not exhibiting Ulay’s aphorisms in this context was a curatorial decision, as they (around seventy aphorisms, each on a single sheet of A4 paper) work best as a whole, as one work, allowing the viewer to get a sense of Ulay’s recurring preoccupations, rather than interpreting each as individual “poem”.

(7) Marina Abramović, Jenes Selbst / Unser Selbst (ed. Nicole Fritz), Kunsthalle Tübingen, Buchhandlung Walter König, Cologne, 2021, p. 96.

(8) Ulay himself referred to the years between 2014 and 2016 as his “Pink Period”. He considered pink as “the colour of his soul” and “the colour that contains the most light”. Pink was a reference to skin colour and his sense of vulnerability and anguish over the copyright issues that arose between him and Marina Abramović, which were later resolved.

(9) These five graphic prints echo the following five Ulay/Abramović performances: Relation in space, Relation in Time, Light Dark, Rest energy, and Point of Contact.

(10) Ulay in conversation with Dominic Johnson in The Art of Living. An oral history of performance art, Palgrave, London, 2015, p. 25.

(11) Ulay in Whispers, p. 89.

(12) Susan Sontag, On Photography, Penguin, London 2008, p. 23.

(13) Following Ulay’s retrospective exhibition ULAY WAS HERE at Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (2020–21), the diptych Soliloquy is exhibited here for the second time ever.

(14) Ulay in Whispers, p. 385.

(15) Ulay in conversation with Dominic Johnson, “Not Reckless but Reckful”, Art Monthly, n. 423, 2019, p. 5.

(16) Ibid.

(17) Sophie Thun in conversation with Daniel Spoerri, Blok Magazine (February 5, 2021), http://blokmagazine.com/now-sophie-thun-in-conversation/ (accessed April 29, 2024).

(18) Ulay often repeats this phrase in different formulations. “The essential motivations in my work have changed, yet remained close the original impulse, the ‘must.’” Ulay in Whispers, p. 116.

PRESS