Eccentric Circling

Colloquially, ‘eccentric’ means something that diverges describing “people and things that deviate from what is conventional, usual, or accepted.” [1] The term can be traced back to ancient astronomy, where it was used to describe the orbits of celestial bodies that do not revolve with the Earth at their centre. [2] Julian Göthe (born 1966) and Anna Zemánková (1908-1986) share an interest in such orbits, in eccentric forms and languages, in imagined and artificial worlds that elude our lived realities, that refuse a common centre. While Göthe focuses on staged means of spatial design, Zemánková creates mysteriously beautiful, sometimes phantasmagorical landscapes. The imperative in the title anticipates that what underpins the work of both artists may be a) the creation of a shared space and b) the increasing aestheticization of our living environments, in which flowers have long since evolved into furnishings.

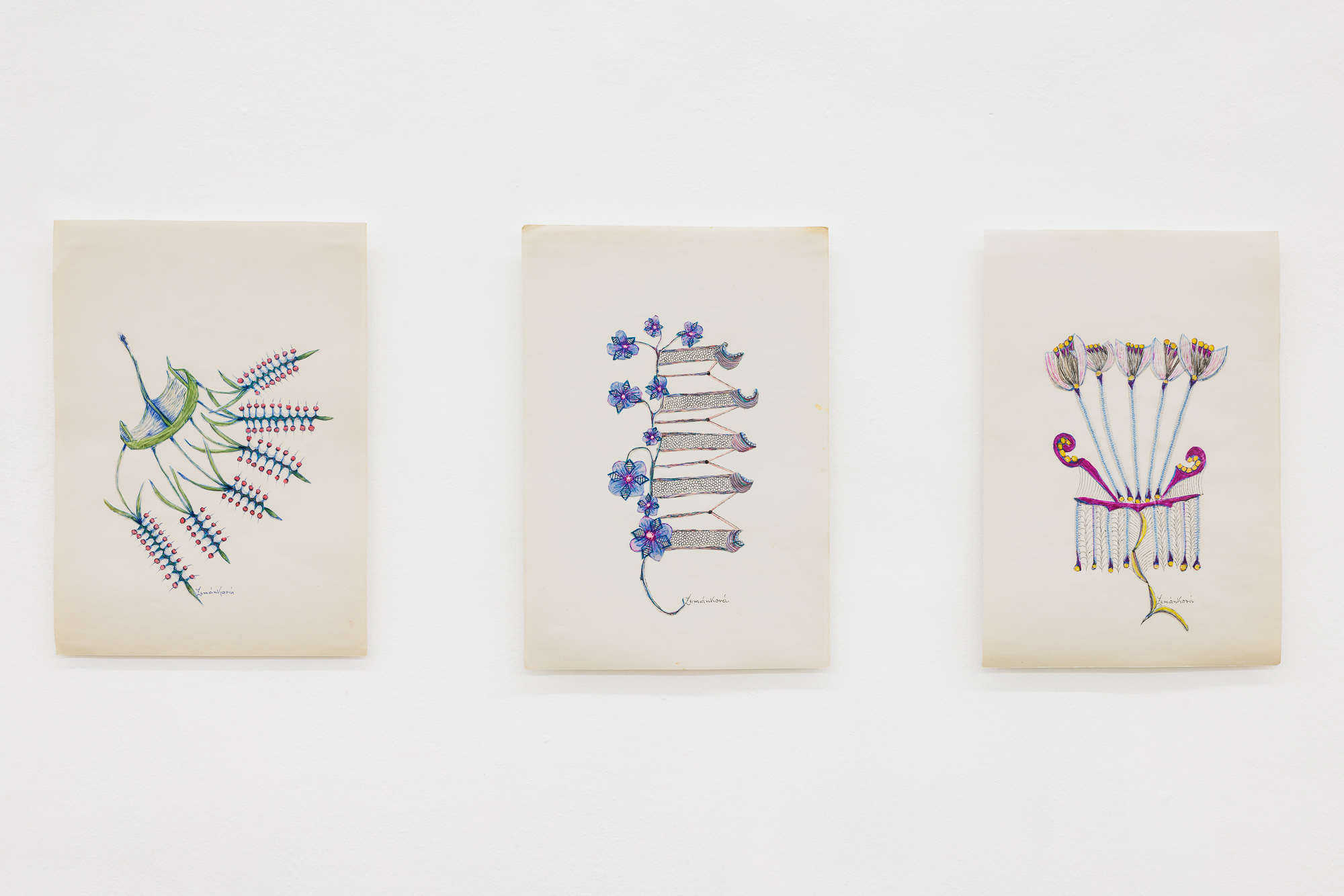

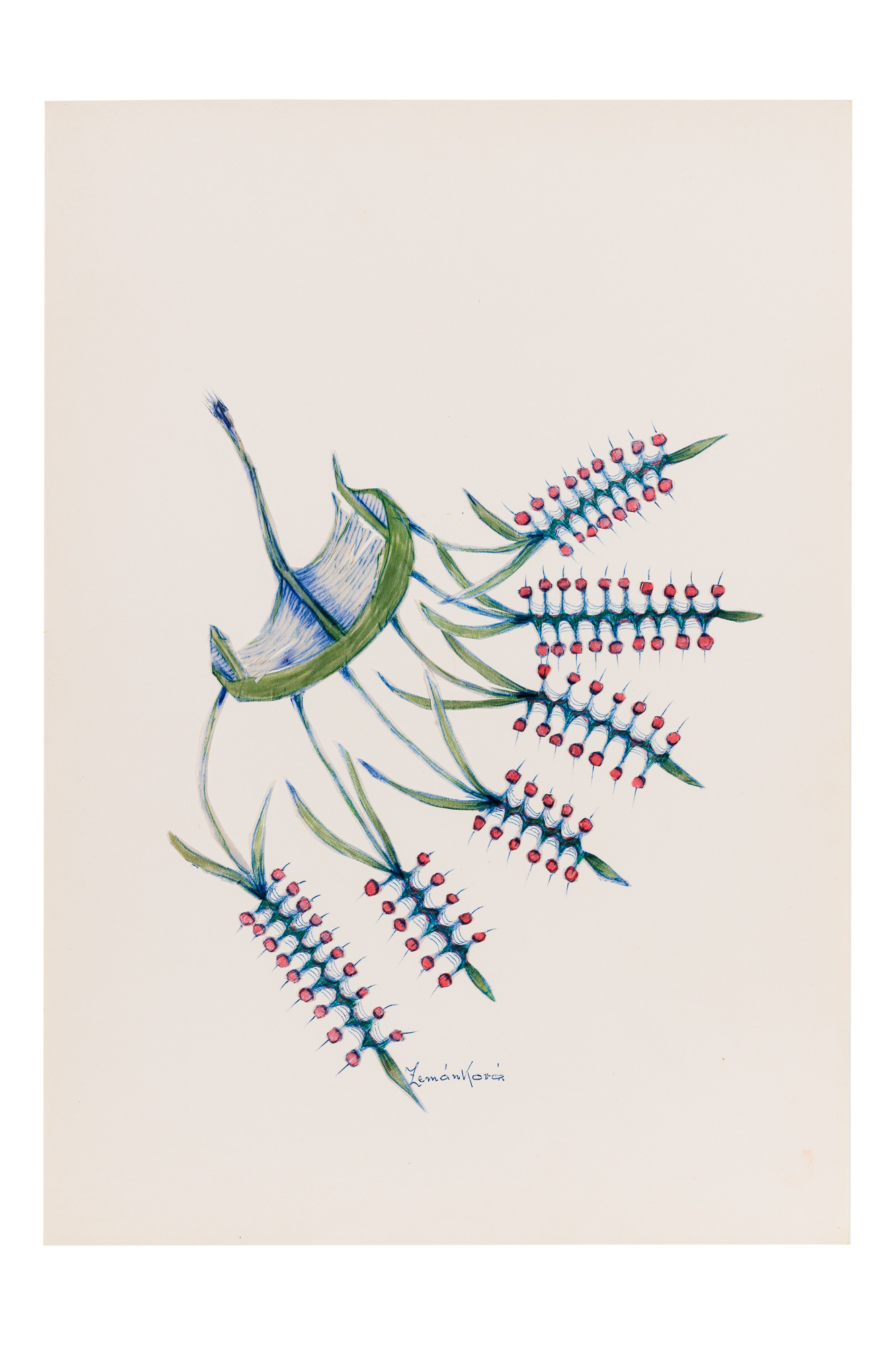

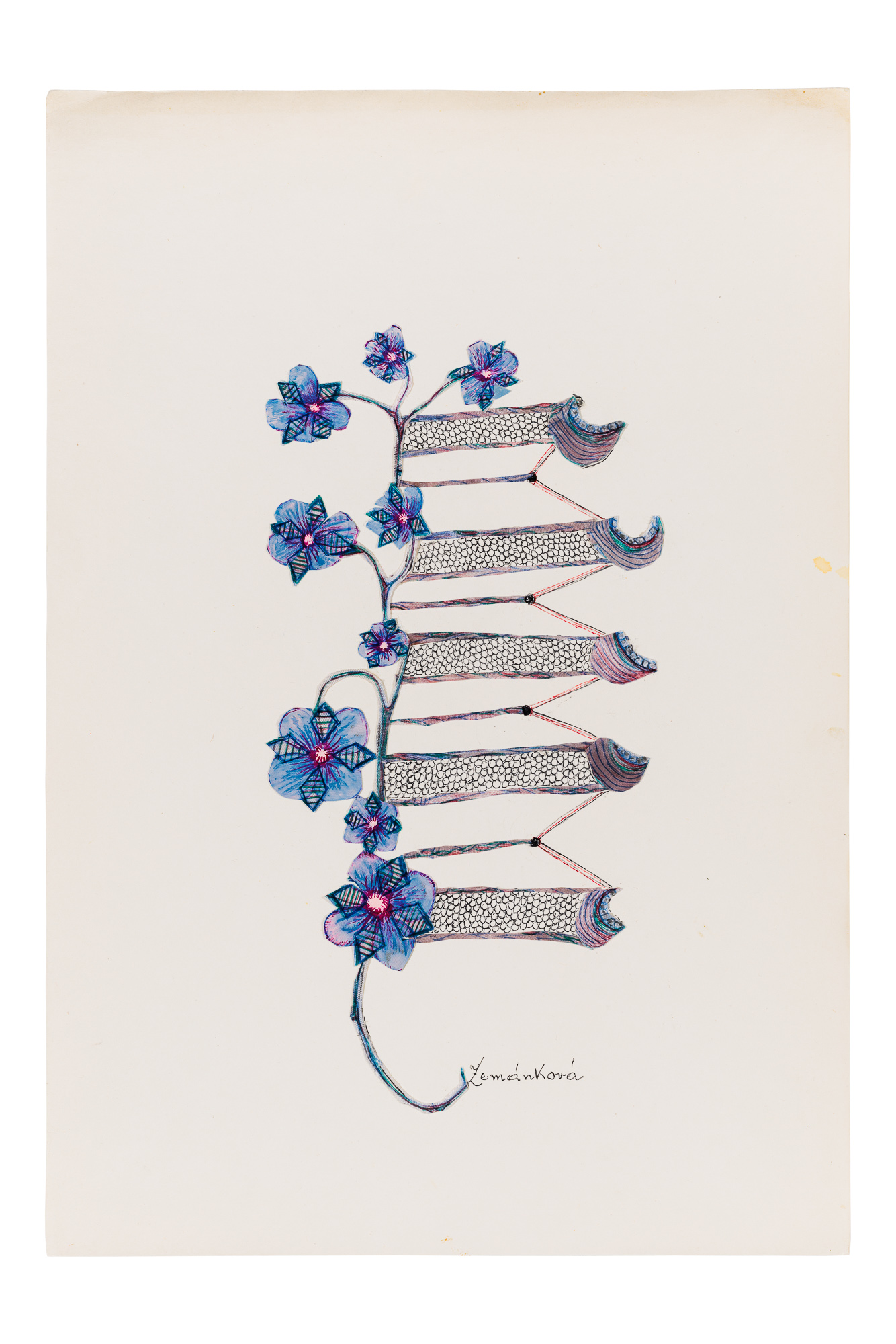

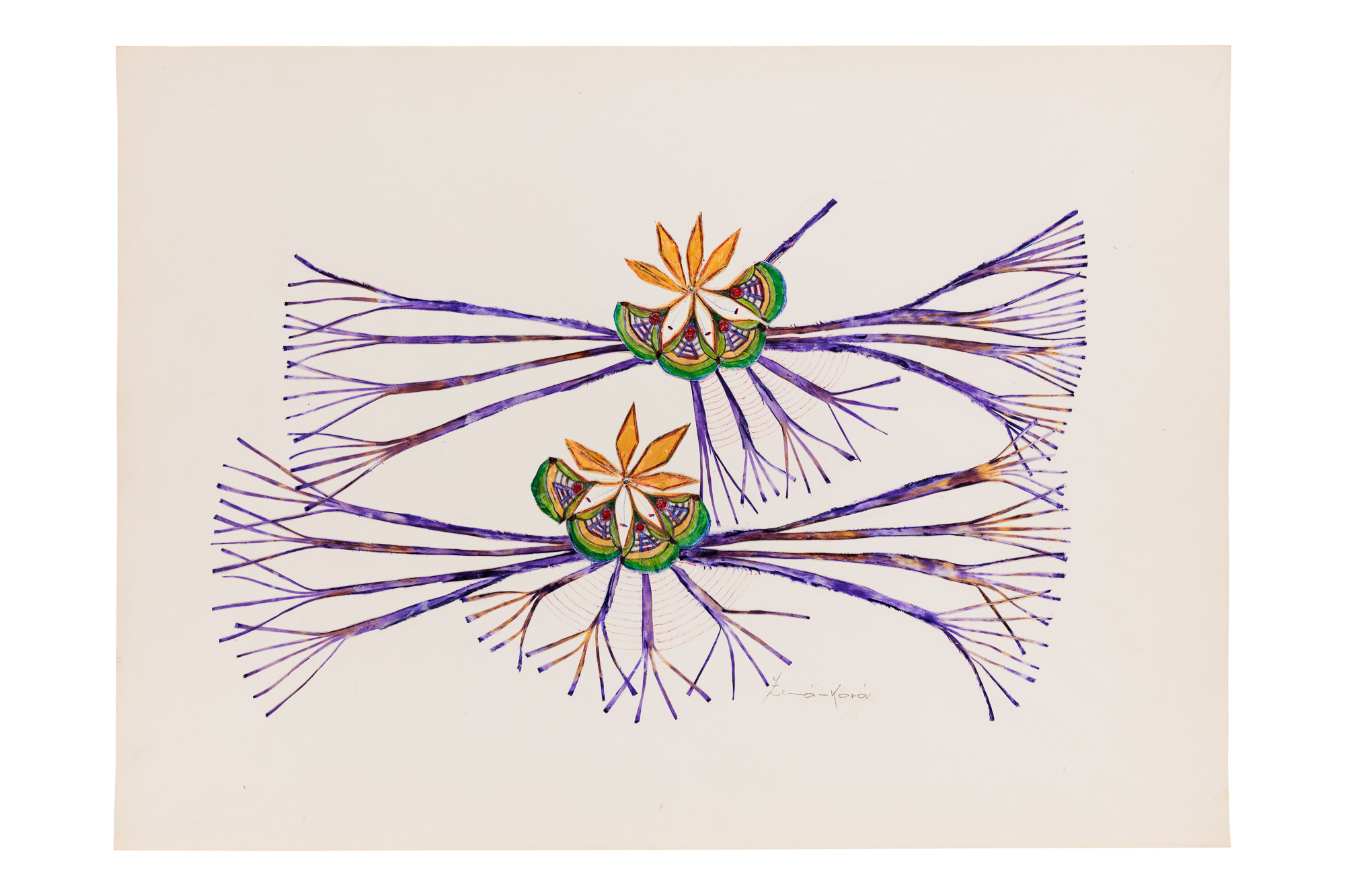

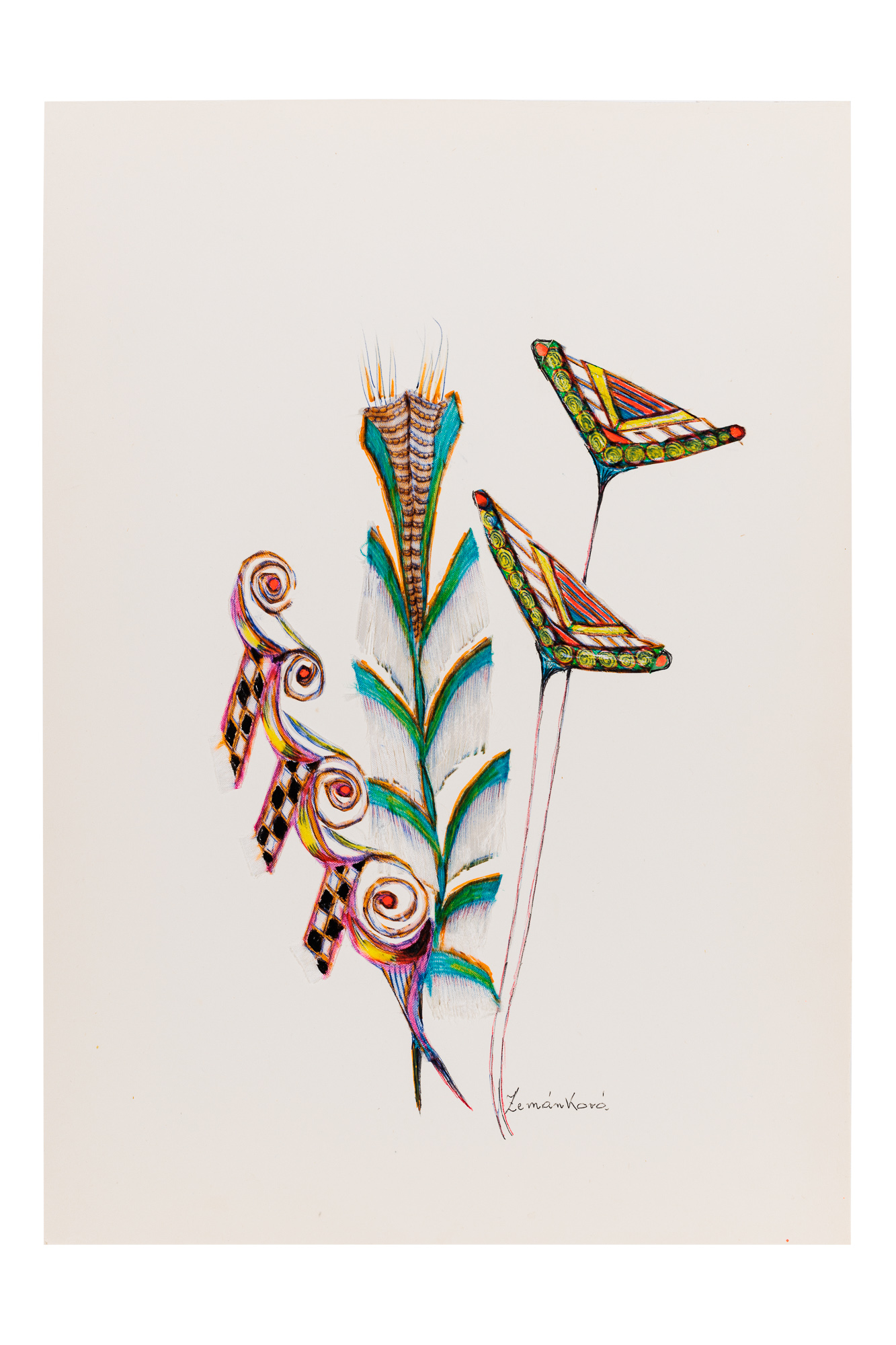

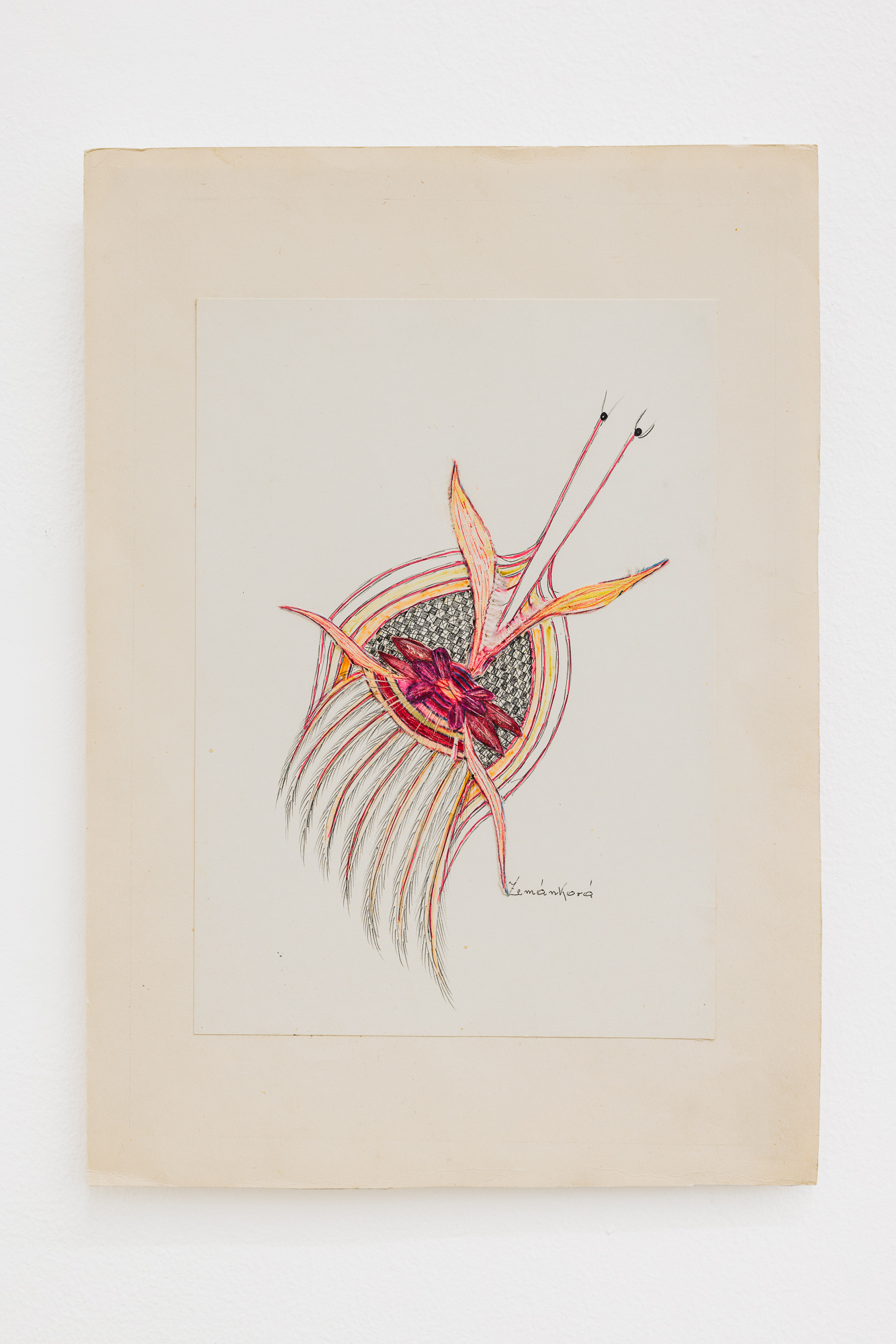

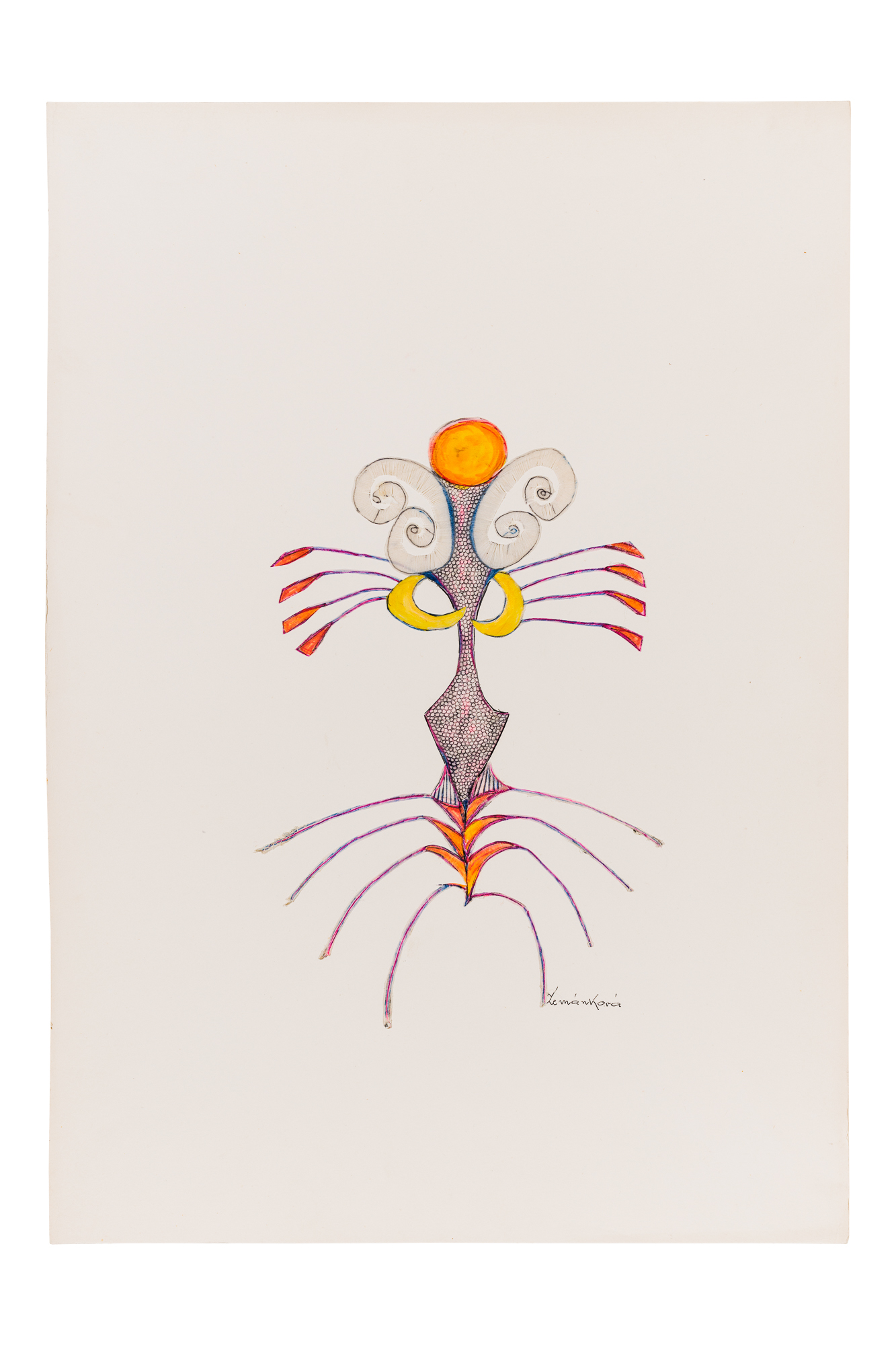

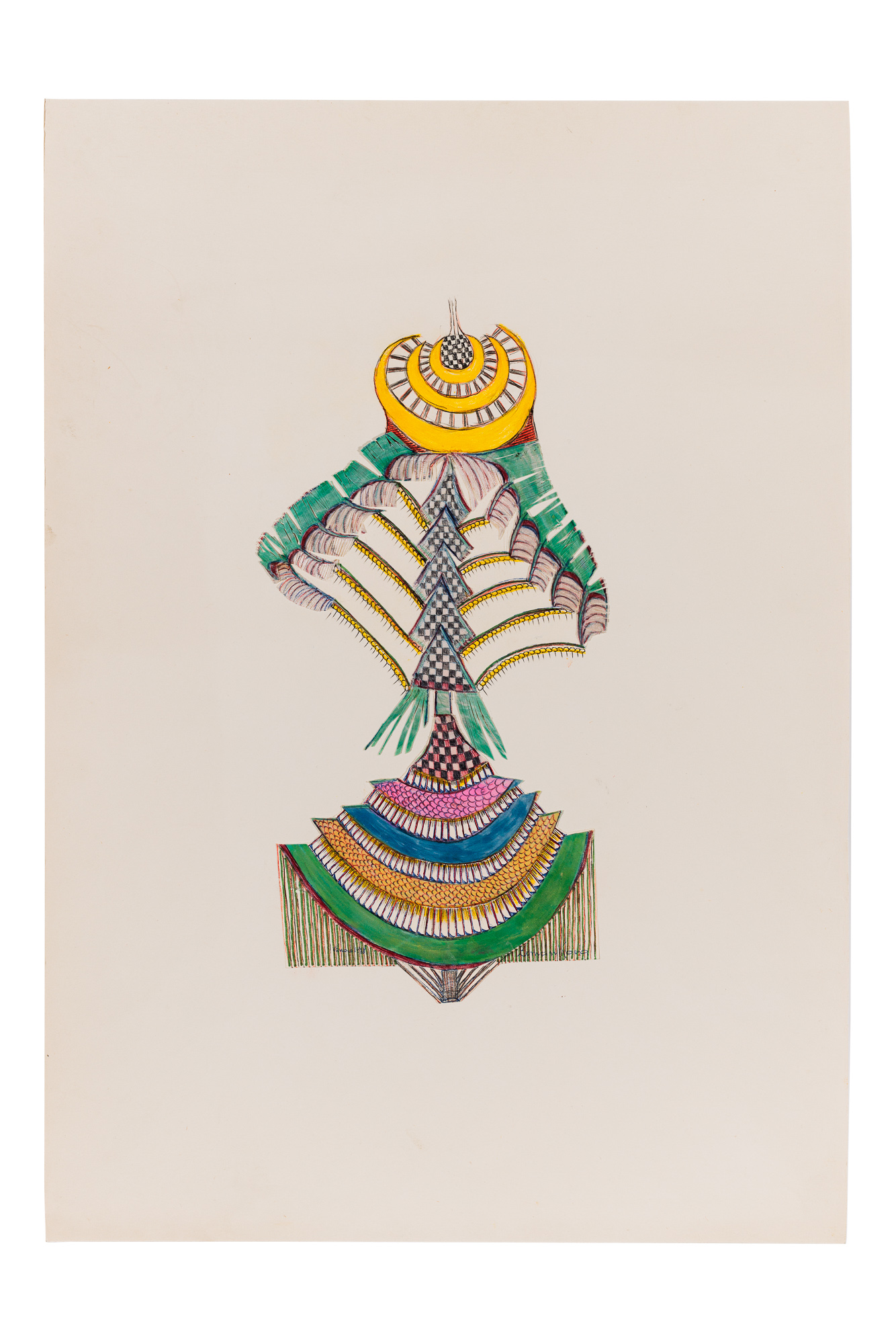

Göthe is interested in the staging of the body in space by means of interior and fashion design. He reflects on the processes in which space comes to be, and questions how space is created, evaporates, and manifests itself. What spaces do we create for ourselves and how do we stage ourselves within them? “Is this intended for everyday life or already part of a play?” [3] Zemánková’s artistic practice is characterised by a similar scenographic interest. In her Prague apartment, she embroidered tablecloths, curtains, and lampshades with floral patterns and placed flowers everywhere. “I remember the all-pervading flood of flowers. Not just the living flowers on the windowsills or in the plastic flowerpots hanging around her flat, but also dust-covered fabric flowers standing in vases without water, with artificial dewdrops on their petals,” her granddaughter Terezie recalls [4]. But unlike an opulent floral still life by Jan Brueghel the Elder, with a rhetoric of transience, or the meticulous, lifelike plant illustrations of Maria Sibylla Merian, in her collages Zemánková seeks ways of expressing inner psychological states. Drawings in ballpoint pen and acrylics, with painted satin appliqués on paper form an artificial flower cosmos that thrives far from external growth factors, blooming eternally. For Zemánková, the discovery of new plant species held an escapist promise of fleeing a reality that felt threatening and often incomprehensible. After the death of her son and further miscarriages, the artist suffered from severe depression. Her children later discovered a case full of drawings she had done as a young girl and encouraged her to take up drawing again at the age of 50. From then on, a strict and routine drawing practice would offer her escape and distraction.

Colliding Perspectives

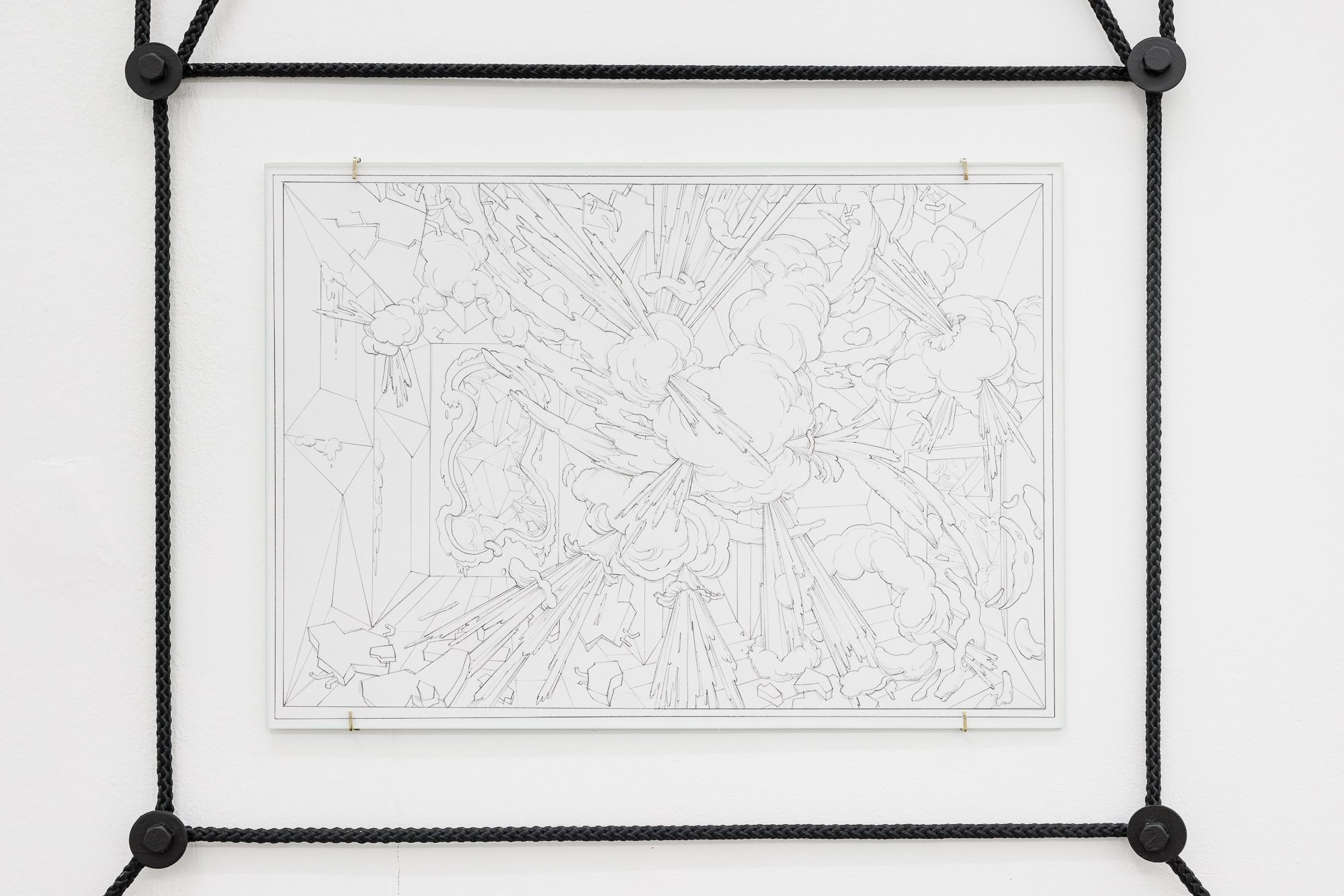

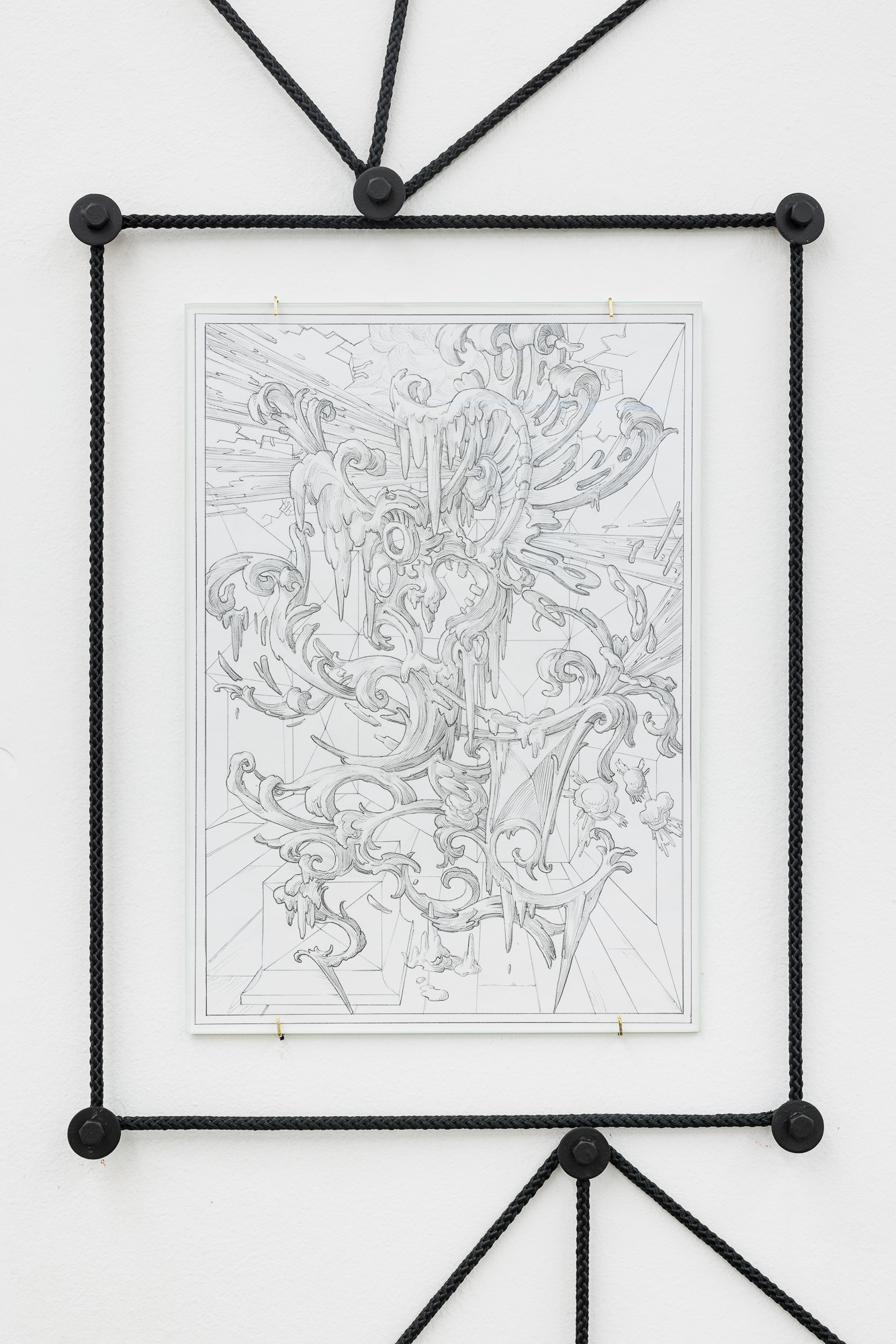

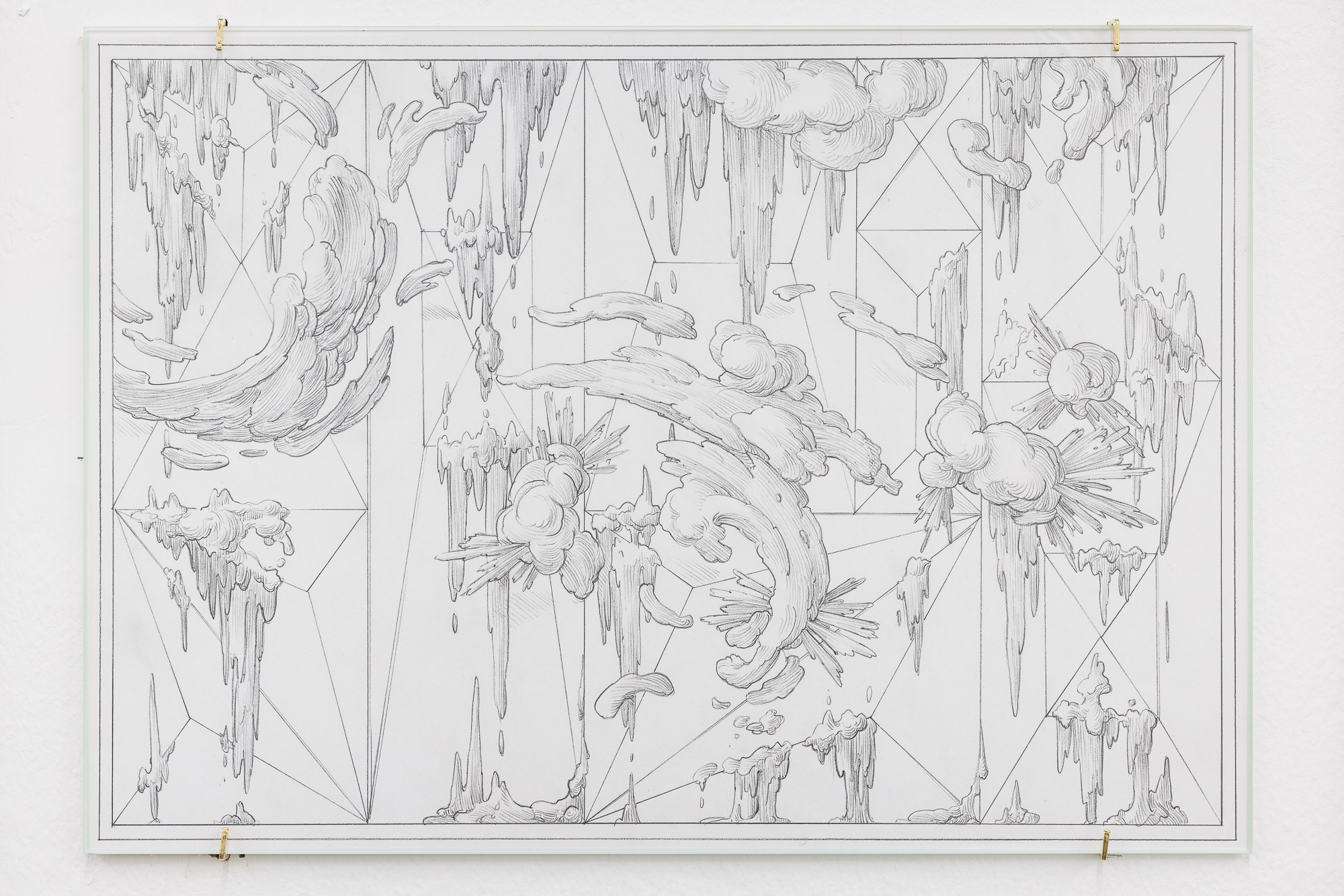

Göthe worked for many years in animated film, the absolute illusionist medium. He worked as a background artist, layout designer and art director. Moments of escapism can be sensed in his new drawings created for the exhibition. You fall in, but can you get out? Where does space begin and where does it end? This also reflects Göthe’s continuing interest in forms that divest themselves of the functional, take up space, and dominate. He draws on ornamentation from the Baroque, Rococo, and Art Deco periods, combines abstract geometric forms with organic ones, and inserts them into multi-perspective spaces. Within them, eccentric activity prevails. Crepuscular rays burst out of clouds, acanthus vines intertwine. Geometric bodies shatter, stumbling aimlessly. Gravity seems suspended, its centre lost.

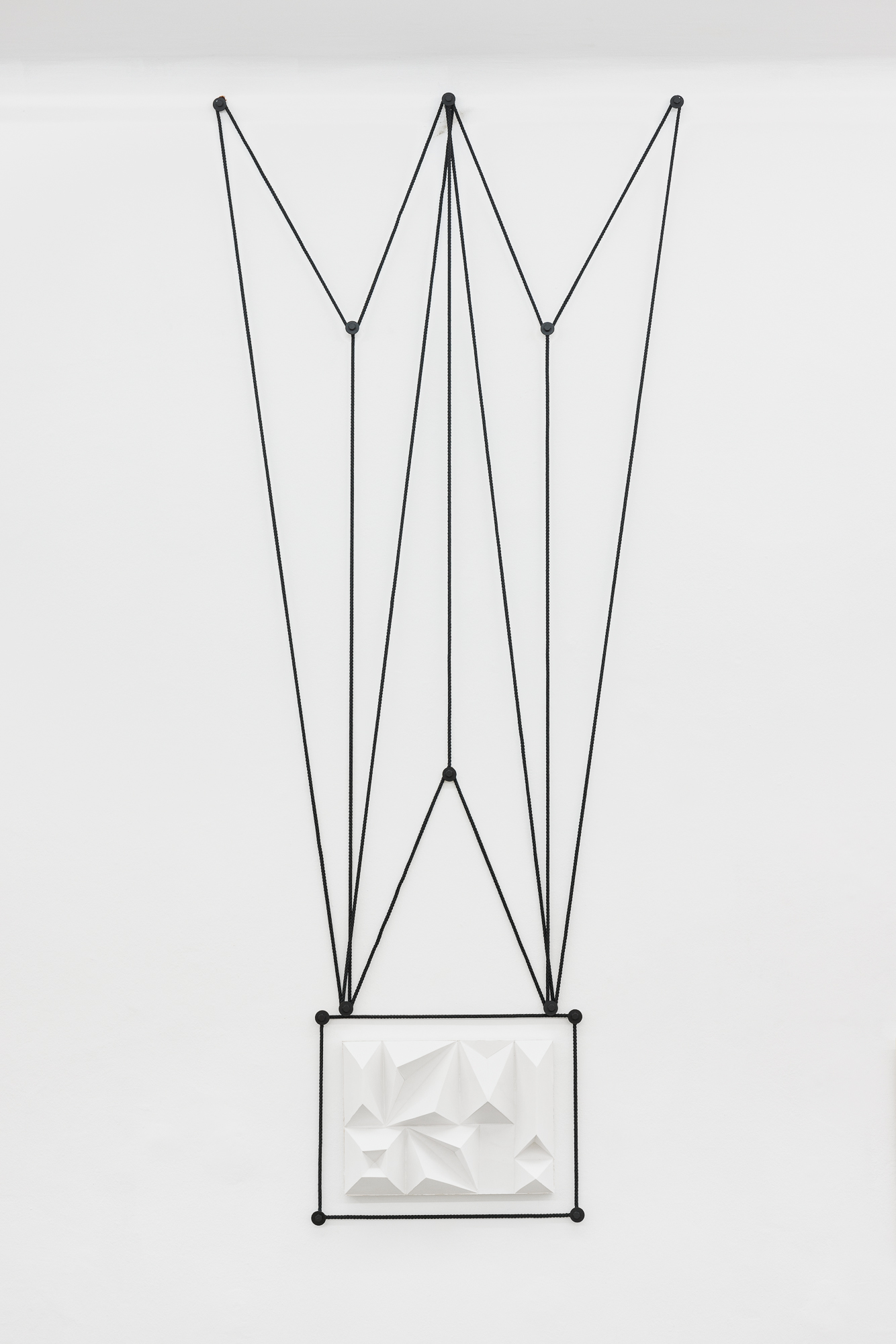

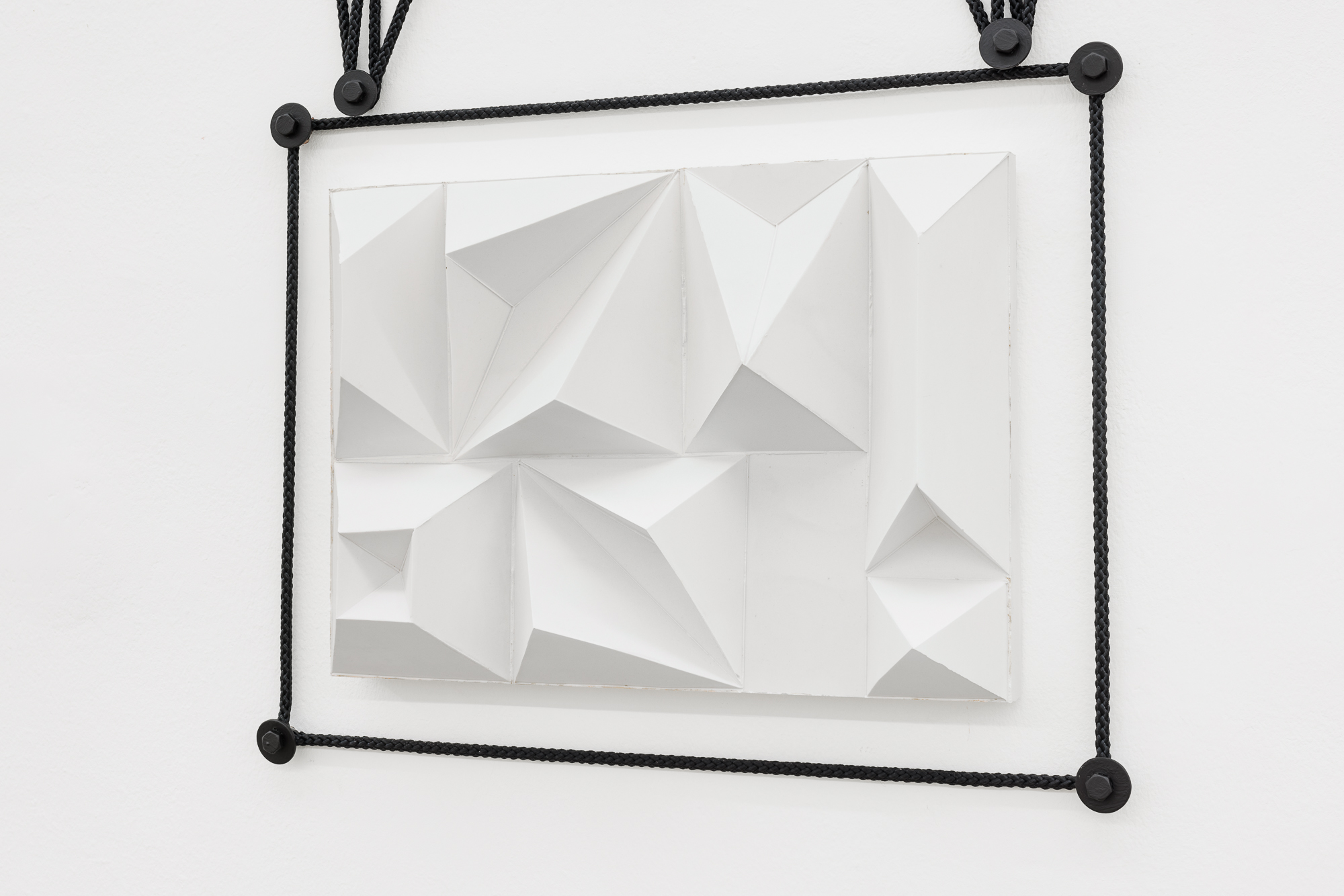

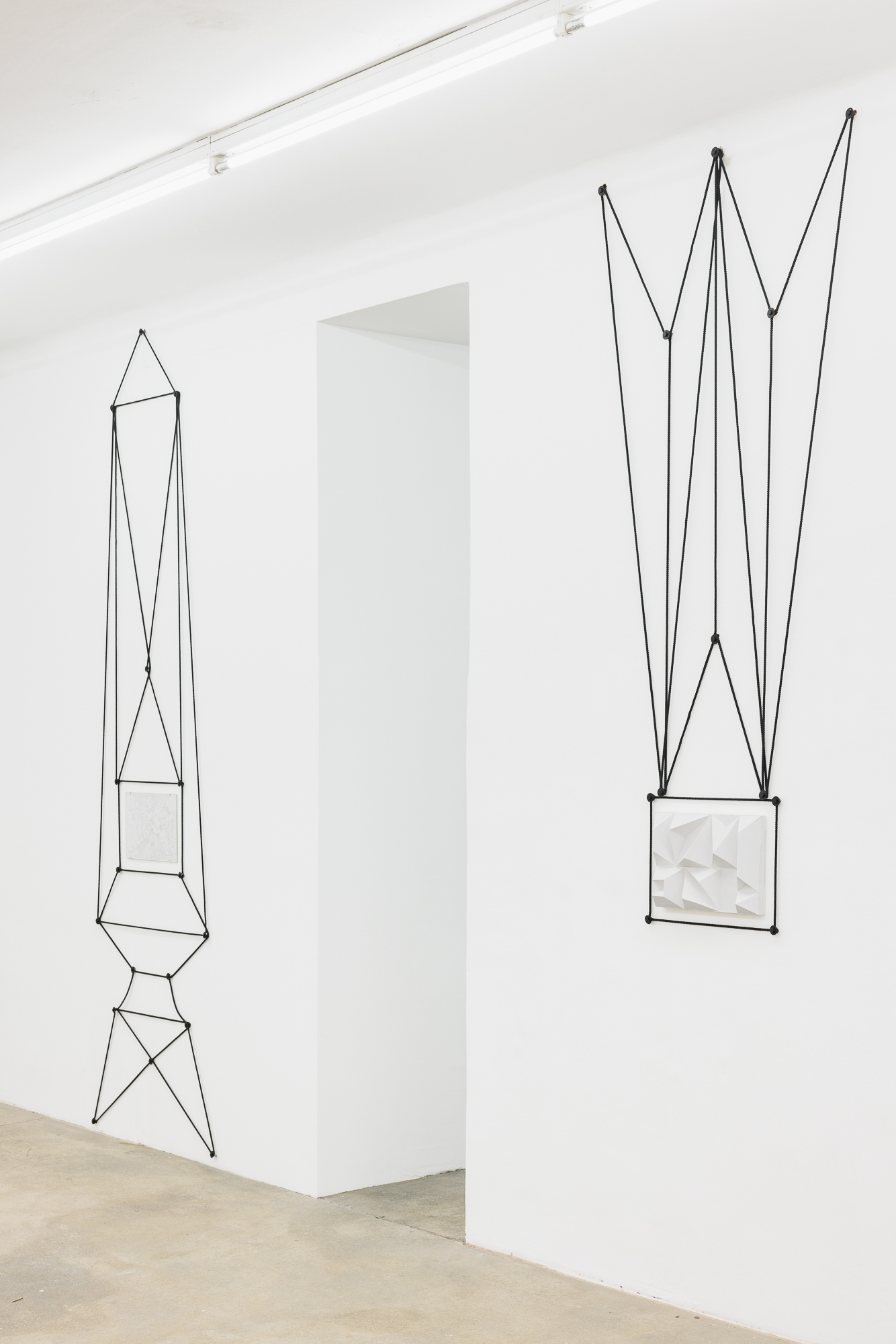

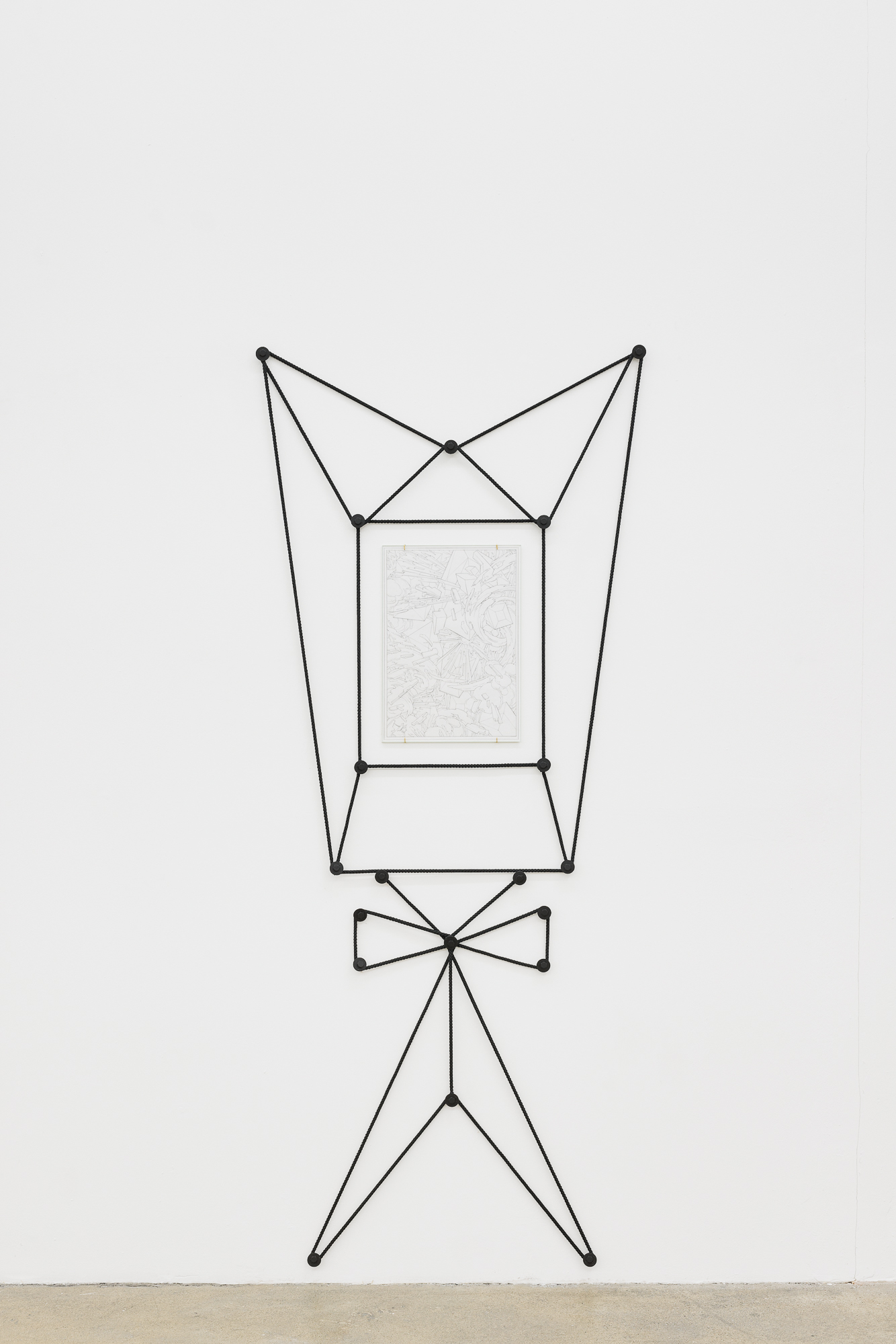

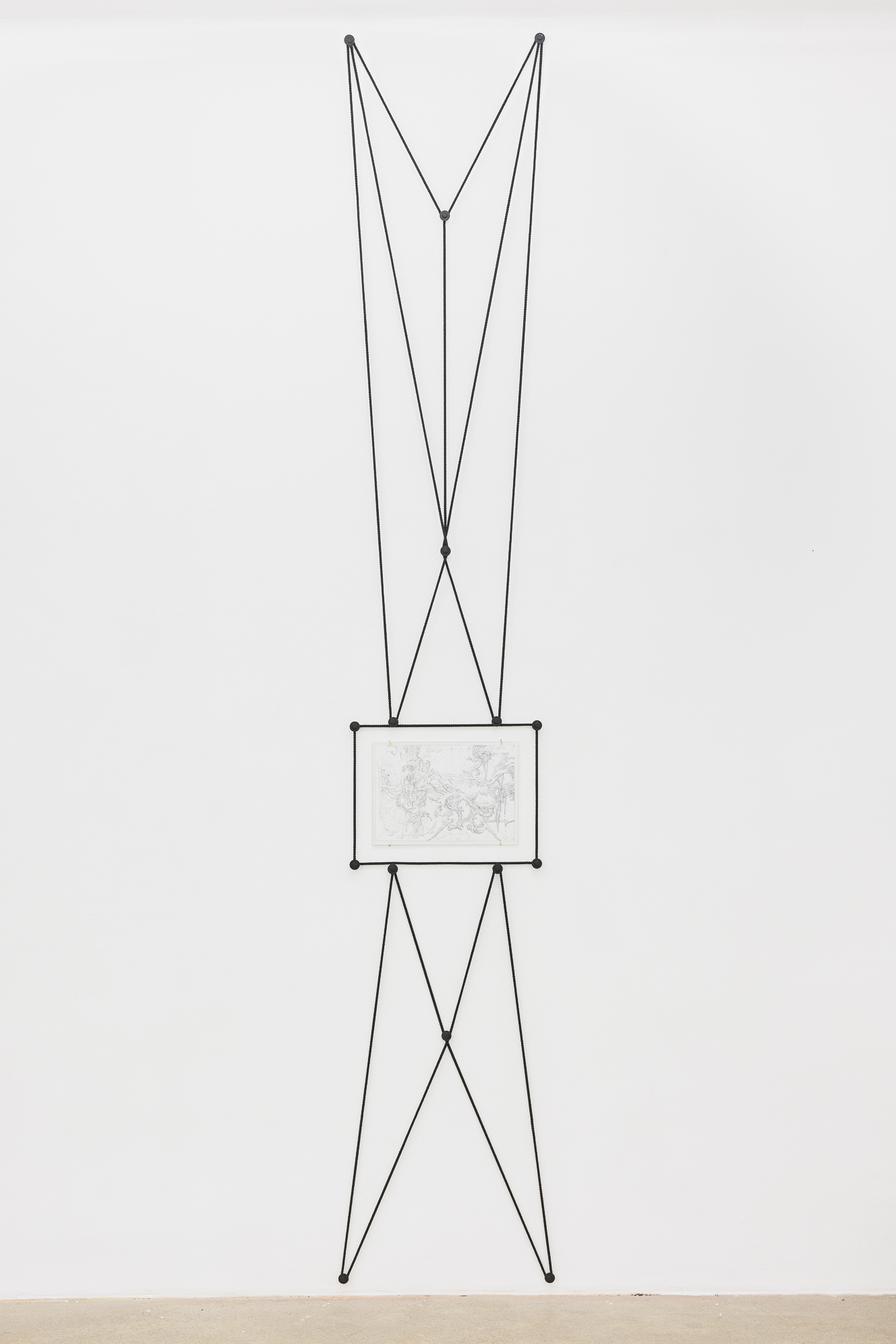

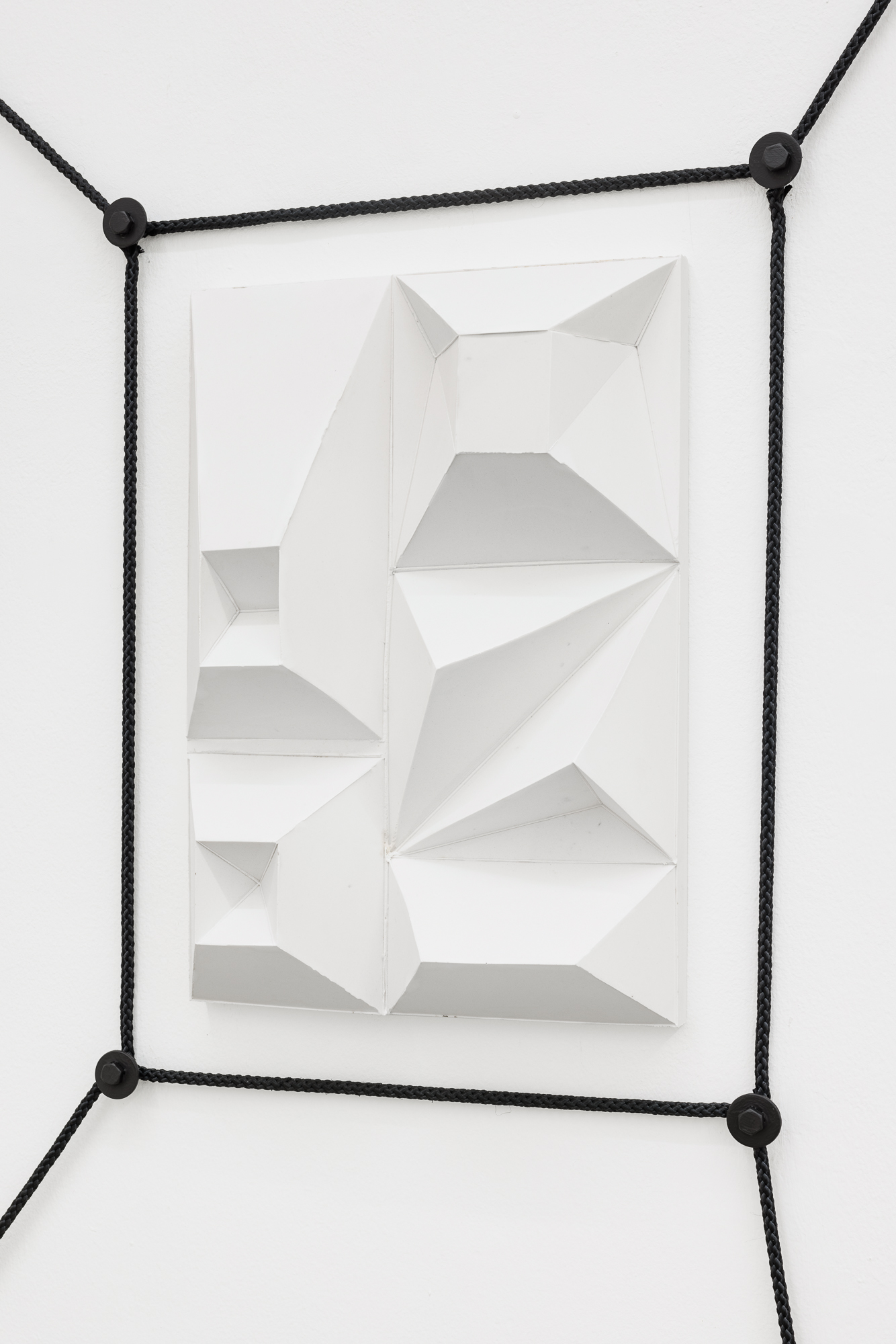

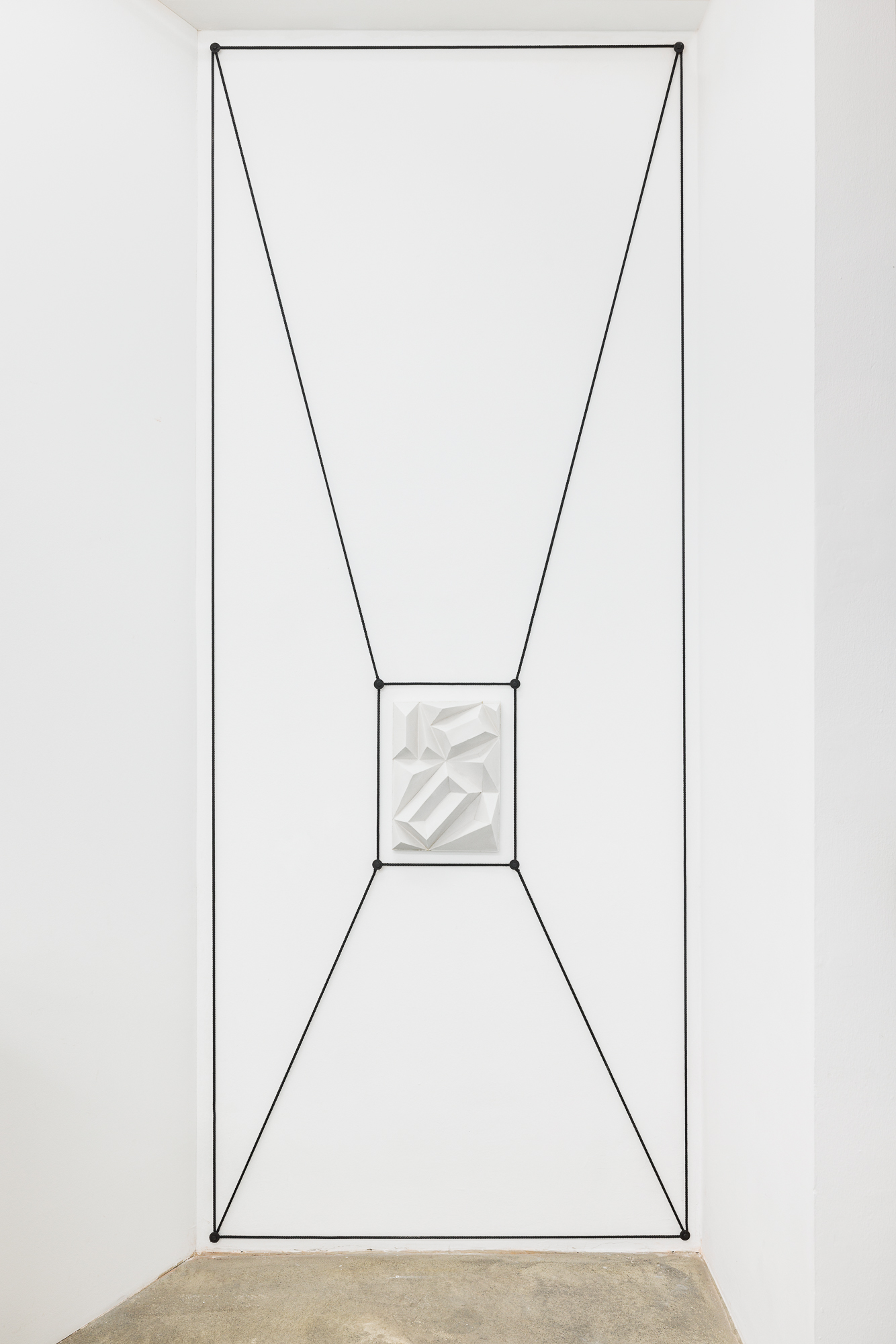

In their exuberant, imposing, and expansive design, the decorative elements also have something obscene, threatening, even catastrophic about them. The simultaneity of the scenes and the elimination of foreground and background mean that neither temporal nor spatial references can be established. The visual order collapses further still. Göthe allows the network of lines to extend beyond the boundaries of the drawing in the form of black cords. They are both framing and continuation, stretching a net on and over the wall that marks and occupies space. The geometric, prism-like plaster reliefs also translate components of the pencil drawing, allowing the two-dimensional to be experienced in space.

Perspective puzzles and displacements are also traceable in Zemánková’s work. While some collages show flowers complete with head, stem, and root, others resemble microscopic enlargements of individual parts or undermine the familiar structure of a plant: Stems are replaced by tiered triangles and softly drawn leaf shapes dissolve into geometric zig-zag lines. She thus divests from traditional classifications and instead creates a poetic-symbolic visual language that manages without words and ascribed meanings. Zemánková’s herbarium forges new orbits.

Liquefied meanings

The title of the exhibition also leads us to a moment of divestment; this is borrowed from the line “Find flowers which are chairs” from the poem Ce qu’on dit au Poète a propos de fleurs [To the poet on the subject of flowers] by Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891). The poem was in fact intended as a mockery, addressed to Théordore de Banville, with Rimbaud criticising the monotony of flower metaphors. Whether Rimbaud was also familiar with the “Victorian secret language of flowers,” which was used to encode and communicate complex love messages using bouquets of flowers in the 19th century, I do not know [5]. But there is a fitting scene in a contemporary adaptation, where, in a library, the protagonist Victoria comes to realise that there are far more dictionaries and therefore meanings of flowers than she had previously known: “The solid form of the chair on which I sat began to liquefy. Without knowing how I got there, I lay on my stomach on the library floor, books spreading in a semicircle around me. The more I read, the more I felt my understanding of the universe slipping away from me.” [6] I imagine Victoria finding herself in one of Göthe’s drawings. She begins to turn frantically back and forth. The room turns upside down. Corridors become endless. Walls fall down behind her, the system collapses. “The definitions were not only different, they were often contradictory.” [7]

The liquefied chair stands for knowledge beyond the supposedly unshakeable, precisely for those orbits without a common centre. And perhaps also for the fact that (our own) staging does not always need to succeed. The Truman Show is not the world we live in. But you are still living in a world of magic [8].

Theresa Roessler

Translation by Morel O’Sullivan