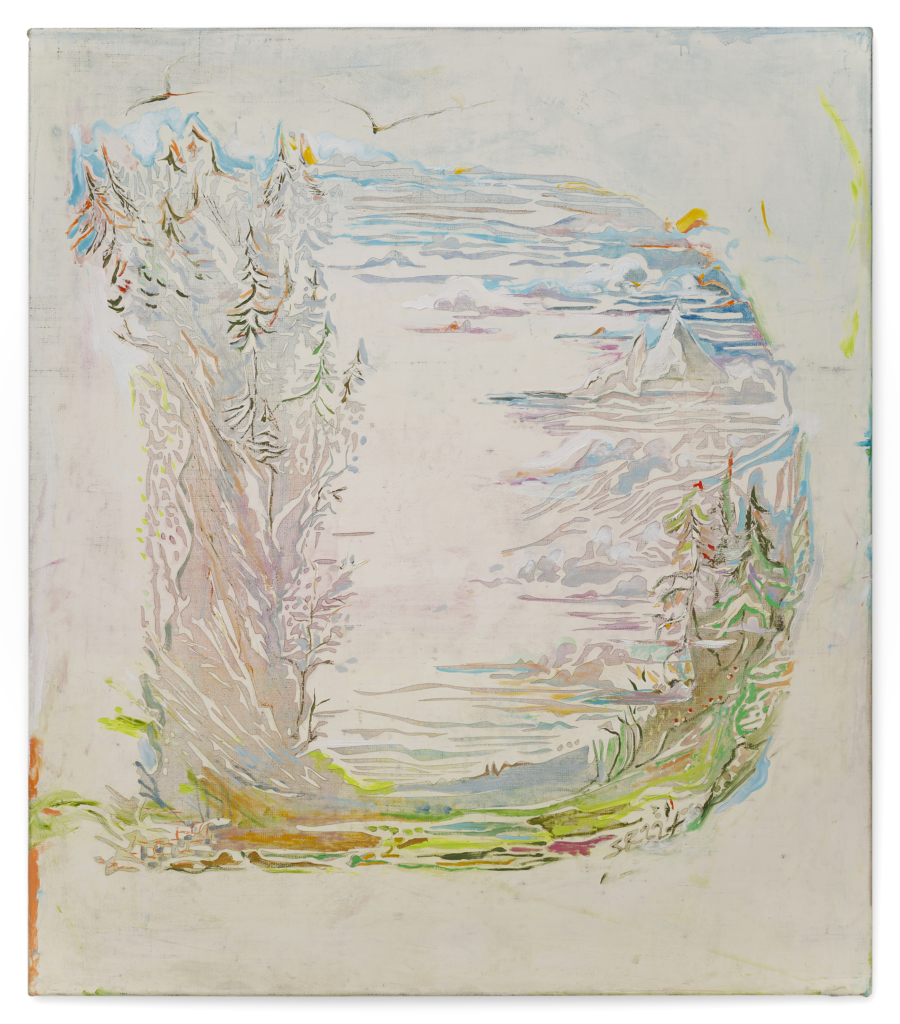

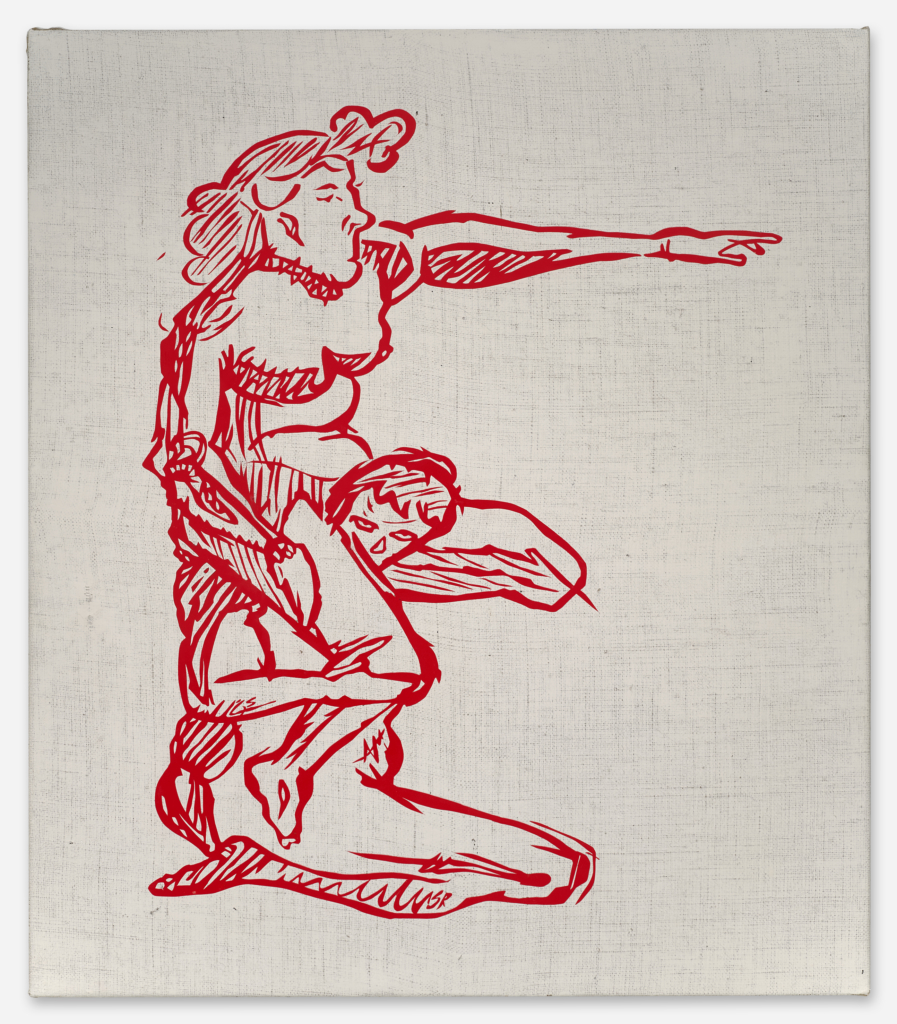

The recent paintings of Sophie Reinhold remind of artisanal building blocks children learn the beginnings of language with. D- E-P-R-E-S-S-I-O-N. The assembled words, from individual pieces, are ones we prefer not to associate with the juvenile, but it’s this mixture of adult and childish, fantasy and reality, opposites and everything, that inform Reinhold’s work. Inhabited initials, the opulent decorations of illuminated pages entwining image and prose, appeared in bibles and prayer books beginning 1300 years ago, but text as a creative and visual act of its own runs from the earliest alphabets up to the novelty fonts we find on our computer’s drop down menus today. That the relatives of something spanning time and culture would be embraced and reinvented by Reinhold makes perfect sense. Her paintings range in style from the romantic to the hardedge. There’s a sort of digital thinking at the base of the work, a contemporaneity that competes with her anachronistic depictions of our collective unconscious pasts. Like the internet, that we can speak of as a unified space, but which holds everything everywhere inside it, her work has a sort of generous greed for all. In her appropriating and altering, while coyly sneaking in her own compositions as if they’d always existed, Reinhold forces ideas and images toward newer meanings. Color and rendering rest deep in the lush marble powder surfaces, but at other moments the removal of that same surface creates the depiction itself. The way words are built is strange to begin with. Single pieces of decorative information, letters, can build so much when forming endless teams together. Over the past year the words APORIA and MENACE have been the foundations of her other exhibitions. Perhaps for Reinhold this is how images build up, endless repetition, unique within their own conditions. The “N” and the “E” of MENACE are different, but also the same, from those in DEPRESSION after all. In her competition of text and image she insists on embedding the original context of these works’ creation, their unifying word, onto their eternity as a work separated from its original family. They collect their own meanings and representations along their way. Certain paintings might not even initially be read as depicting a letter, only revealing a possible further legibility in the company of others. In her choice of heavy words, ones that affect us all as we move through life and society, she speaks to one of the high duplicitous truths within art. How much enjoyment have we received from paintings across history born from the negative? Memento mori, broken hearts, and, of course, depression? In admitting that poetry and joy might not only be birthed from these moments in the eyes of an artist, but also built up from them like those same blocks and letters and words, Reinhold remains lucid and visionary about both the heavenly and earthly.

by Mitchell Anderson