Anna Zemánková said that she exclusively created flowers – apparently, she felt a natural affinity to them, surrounding herself not only with fresh flora but also its plastic counterparts. Her fertile, colourful overflow of drawings, paintings, and collages overwhelms and can even occasion delirious nausea in the fortuitous curator examining her sizable archive. What makes her story so fascinating is that it began quite late, around the year 1958, when she was about 50 years old. Back then, her sons found a small suitcase in the attic that was full of simple paintings. When they learnt that she had painted them, many decades ago, they persuaded her to take up work on paper again, for amusement. Their mother was going through a personal crisis and experiencing long-term discontent; her children had long left the nest and didn’t require her care anymore, while the relationship with her husband was disharmonious. She was holding in an inordinate amount of energy that needed to explode.

Her yearning for creative realisation arrived out of the blue and only began as a means of self-preservation and pleasure – the meticulous labour brought her satisfaction and a deeper potential for becoming “her own person”. Soon, diversion became a necessity. She would wake up around four in the morning and start to paint while listening to classical music, unable to create in silence. Her hand first covered contours of the largest volumes, then it turned to shape the smaller units, and finally, it came upon the lacing of tiny details. Her former practice as a dental practitioner manifested itself in her meticulousness – in the filigree fillings and arabesques of her artworks.

Anna’s creative impetus originated somewhere deep inside and was an intuitive, rather than rational process – once her hand had drawn a shape, that shape instantly birthed another. The author claimed that she could not trace the exact source of her imagination, nevertheless, the work encouraged her to free herself from matter and to harmonise her soul. Although these facts might evoke spiritualism in art – Hilma af Klint’s works might surface in the mind’s eye – she never spoke about any divine power at play. Being a self-taught artist, she had to devise her own method – the faith in her ingenuity became her driving force as well as a source of pride.

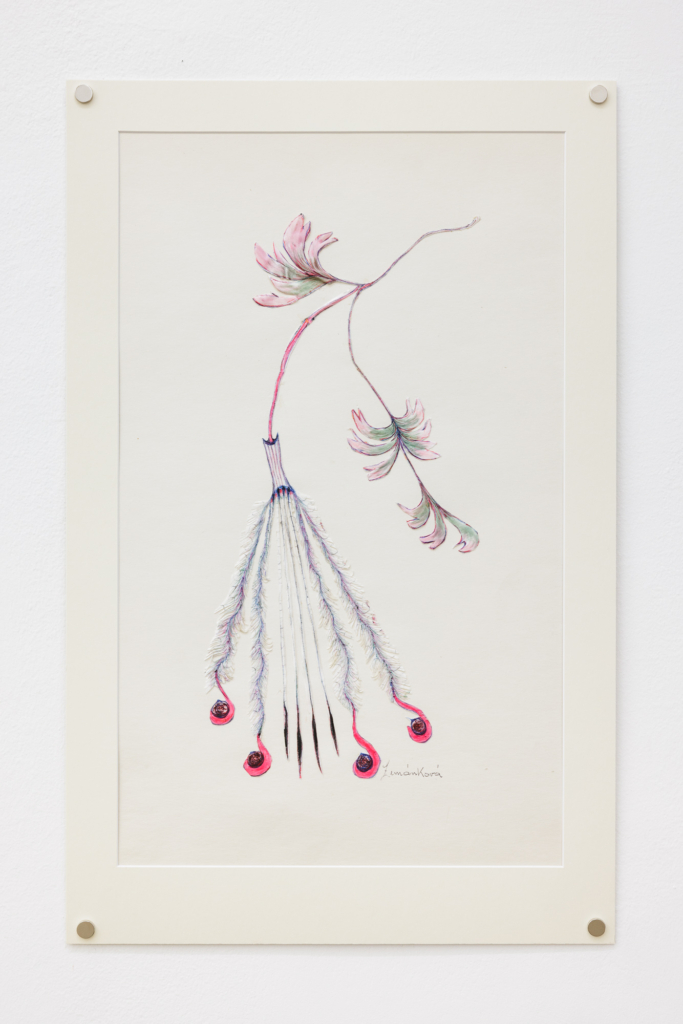

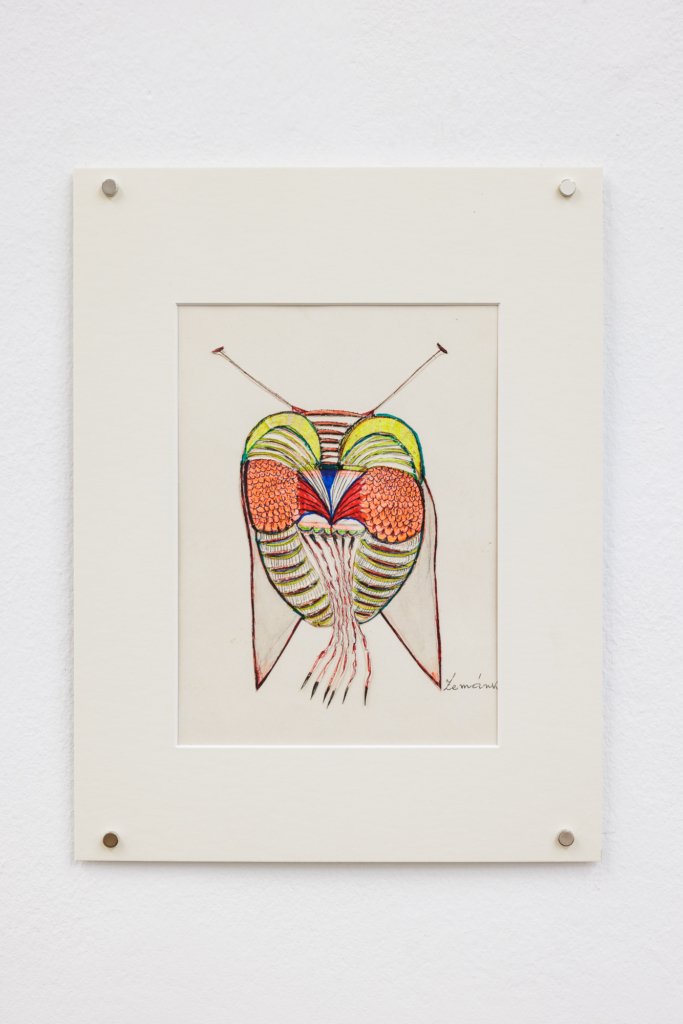

We may assume that her aesthetic preference was informed by the folk costumes of the Haná region, herbariums, memorials, the exalted quality of baroque, or perhaps even the decorative curves of art nouveau. However, even a mere glimpse assures us that these plants were not formed from terrestrial matter. They often vibrate with an ominous mystique, and in her drawings, we may occasionally observe alien bodies and formations (she was a firm believer in extraterrestrial civilisations). It is sometimes unclear whether we are standing face to face with objects of orders of magnitude a few times lower or higher – witnessing tissues and division of cells, seaweed, amorphous protozoa, or planetary explosions. This mental vegetation defies the laws of physics, and the only thing binding it to Earth is that it indeed usually grows upwards. Otherwise, it exists in a vacuum rather than in humid air.

Anna took pride in her unique and nonrecurrent output; permutations of vegetation as language, inner structure, and subject of her work. Various authors dealt directly with ontological processes and the libidinal desire to self-impregnate in their interpretations of her work because the world of plants naturally invites such reasoning. However, the matter she created is otherworldly, more enticing and succulent than nature itself – at times, even sinful.

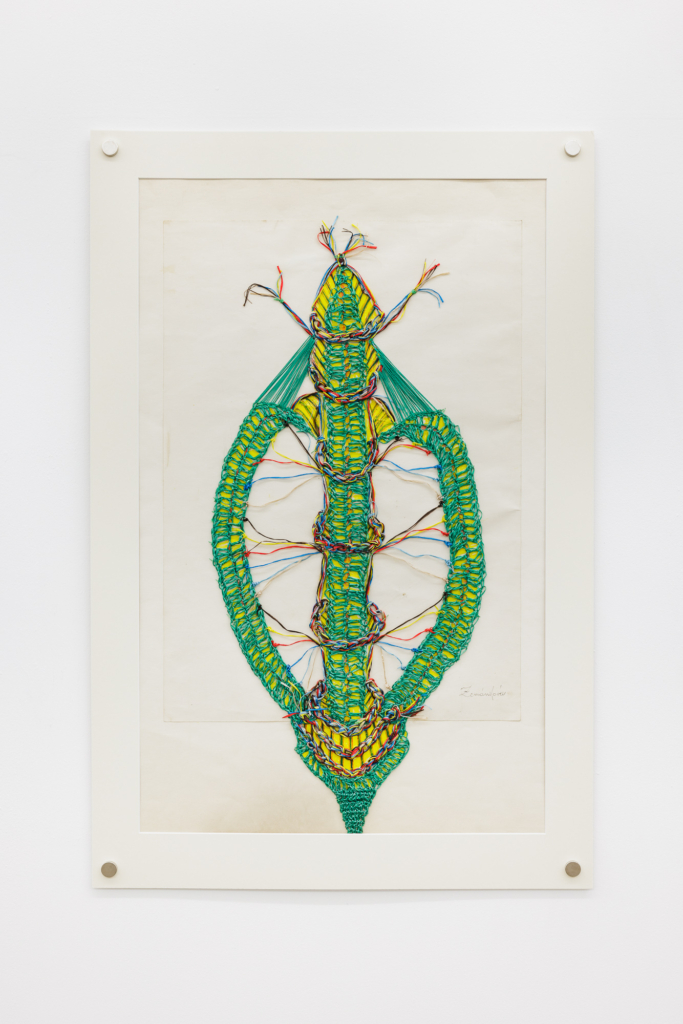

The artist discovered, even invented techniques on her own terms, not having received any formal art education. Initially, she worked with pencil and tempera paint, watercolour, then with dry pastel, oil pastel, and crayons. There was a time when she used to cover her drawings with cooking oil to seal them and provide translucence – it didn’t occur to her that the oil would soak in and leave an unsightly stain around the contours. She composed collages out of paper snippings or satin, then sewed beads and sequins into them. With a needle, she punched through paper and embossed it with reliefs.

At her home in communist-era Prague, she built a private “fairytale kingdom”, surrounding herself with kitschy things. That’s because – according to her family – she preferred conventional beauty in her living space. In her artistic practice, it was the other way around – she seems to be bolder in her creative expression. Often, she had to exert an almost superhuman focus to produce tens of thousands of dots and lines in the drawings’ details, without errors and smudges, with the skill and rigours which would have also been necessary for her former job.

Hanging directly in front of the gallery windows, we encounter perfect specimens of such focused work. The perforated pieces react to the sun outside, which occasionally nurtures them with its light and reveals their secret innards. Through their slits, we observe the clusters of stars and cellular divisions they contain, and imagine reading their incisions with our fingers. At points, these dots are so close to each other that they almost meet, so dauntingly on the verge of tearing. And just like ferns with porous sporangia that have opened, these pieces, suspended for the first time, presage the germination awaiting inside.

Next to the gallery door, an extravagant perforated work materialises in watercolour and ballpoint pen a form suggesting congenitally malformed birds of paradise, discharging small tousled blooms of paper, their contours delineated with string. Anna usually pierced two sheets of paper atop one another. She shaded the upper layer, adding a pastel-drawn frame to the resulting colourless lace-like imprint which formed underneath.

On the altar for the colour blue that shares the same room, the shapes are oozing and vibrating with electricity. The work stands at the beginning to mark the birth of light, as a weightless outburst of ontological radiance. Anna was fond of the ornate writings of the Czech symbolist Otokar Březina whose words seem apt to characterise the pastel drawing:

For even the labour of the earth, the crudest and humblest, where man and beast walk side by side in the disc of one hot breath, has its feature of pathos, its lustre of painful glory, the ecstasy of self-forgetfulness, its intoxication of the wind, mixing the spiritual breath of millions and in the sleep, the thunder of a gigantic pulse, like the resonance of the anvils on which worlds are shattered and shaped.

Indeed, radiance surfaces as one of the recurring themes of this project, whether as photons sieved through perforations, depictions of glowing material, or lamps which literally emanate light.

Anna’s works were all conceived during morning seances, in the rift between night and day, between dreaming and wakefulness, on her kitchen table. She showed them mostly during self-organised Open-Door Days at her home-cum-studio, for which she would hang her artworks on the walls, on improvised boards, and even on wardrobes. She invited her neighbours as well as her children’s friends from the art world. While this exhibition doesn’t attempt to simulate a home, hopefully, echoes of domesticity aren’t lost on it, either. Artworks like these usually find themselves in a more formal environment, more often in modernist contexts like art brut than contemporary art, adorned with a passe partout, and framed to be displayed under glass. Here, we meet them almost naked, which renders them in some way unencumbered, youthful, perhaps even more honest. The project also attempts to bring to light parts of her oeuvre that often stay hidden, and in truth, the associations and projections of the curator as well.

On the back wall in the second room facing the street, the curator’s flamboyant inner child takes the liberty of assembling a sartorial cast of semi-anthropogenic protagonists, meeting for the first time. Present here is the elegant lady donning an emerald-hued art deco dress, whose walk exudes elegance, posessively chaperoning her jolly debutante daughter. There is the dazzling samba dancer in her headgear (whose crumpled skirt I had to frill and style myself, thank you very much!), and lastly, rubbernecking the scene, the slender ballerina, who may as well just have been a simple flower, turned upside down on a momentary authorial whim.

The character that I imagine is missing is Anna herself, as a flower in a long white satin dress, supposedly with a metres-long train on her wedding day. (Later in life, the artist would use the same material as her wedding dress, artificial sateen, starched, cut, painted, and glued to form one of her creations.) Instead, it’s the dominating corset that benefits from both camp and lascivious satin sashes, both adorning and binding. Right across the room from it, we notice the totem of a wondrously festive phallus of satin, splitting in half, as a bitterly humorous reminder of a matrimonial fantasy turning sour.

Some of the artist’s most monumental pieces are fascinating, complex, self-contained, tensed embroideries, hosted here on the longest wall. Among them, the crocheted, crisscrossed, upside-down monstrance holding relics of colourful plastic beads in a grid of sacred geometry, conjuring a suprahuman ornament.

Anna embroidered not only her works, but also her curtains, tablecloths, covers, pillows, all in her fantastical home, where art met function. In another first, the artist’s parchment paper lamp works are exhibited, oscillating between objects of art and furniture, to radiate their own light, as precariously sewn onto their metal stands as they would have been by the author herself, who also managed to burn some of her lampwork while working with electrical wiring.

Anna’s son Slavomír promised to bring her his collection of tropical butterflies, but it never materialised, which is why she decided to draw them instead, as if to conjure the real entities through their representation. Merging with birds, butterflies, manta rays or fans, these contrasting pieces are a pure delight. One butterfly seems to merge perfectly with a dress, marrying the existence within a tight, restrictive cocoon and the perceived freedom of a butterfly in flight. More butterflies still, this time in pencil and on a single panel, completely fill out the holes they’re given and without a distinct background end up looking like tarot cards, or a hieroglyphic alphabet.

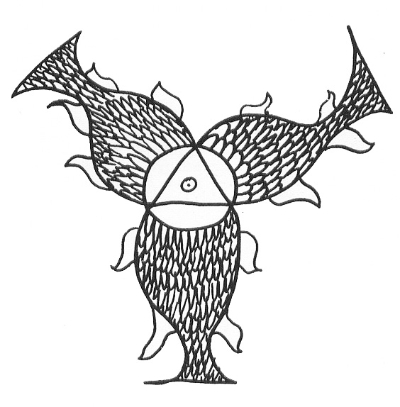

When Allen Ginsberg gifted her son Bohumil a drawn triquetra of fish symbols sharing one head with an all-seeing eye, which the American poet and writer would adopt as his ex-libris, Anna produced this large pastel work of a fish as her intuitive response to it. Anna Zemánková herself had glaucoma – a common eye condition whereby the optic nerve connecting the eye to the brain becomes damaged. While it was easy to treat with a daily dose of eye drops, it must have been tragic to live in fear of the gradual loss of sight, especially having begun her career as an artist at a late age. The edges of her vision slowly faded into the dark. Perhaps as a result, the artist also tended to darken the margins of her pastels, too.

On the lower floor, in the dimming light, we experience some of her latest works. In the twilight years of her life, first one and later the other leg had to be amputated because of her diabetes, and she moved to a retirement home in Mníšek pod Brdy. Here, she would continue her work with a wooden board placed on her thighs and, due to the limited space and motoric skills, go on to create increasingly minuscule artworks. She continued making these stamp-sized, simplified echoes ofher previous flowerwork until the final moments of her life. Myriads of her flowers would continue to blossom on her friends’ and children’s walls, as well as those of different museums and galleries. Unlike real blooms – and human bodies – they would never wither.