Lemme tell you a thing or two about camouflage; while this is the title of one of the works in Sophie Jung’s exhibition It’s Not What It Looks Like, please allow me a few lines on attire.

Although it is often said that “the clothes make the man”, it’s not without merit to note that this glib adage is a bastardization of Shakespeare’s “for the apparel oft proclaims the man”. More than mere sales pitch, the playwright’s line is just but one contained within a longer piece of advice wherein the character Polonius tells his son to live honestly and within his means—the lecture follows with the more frequently quoted “to thine ownself be true”. As platitudinous as this domestic scene from Hamlet may seem on first blush, it also portrays the hypocrisy of the speaker, an ostensible apparatchik spy for the play’s murderous usurper king. Balanced against the work as a whole, Shakespeare’s irony hints that public displays may hide private interests. In political theater the rub between what is broadcast, and what is withheld for those with “in the know” privilege should be resolved through a form of disclosure known metaphorically as ‘transparency’. While this standard attempts to hold corporations, overnments, or even museums accountable, it wouldn’t be ideal for you to show up to the gallery aked—amongst other things, you just might catch a cold.

Eschewing concerns of production here, communist designers such as Alexander Rodchenko, turned to the uniform as a way to universalize fashion so that everyone, more or less, would come as they are. Whatever good such outfitting could bring, it also presents a rather drab, let alone dehumanizing, existence. Conversely, the total freedom to wear whatever one’s heart desires might allow for one form of self-expression; however, it too can misrepresent other characteristics—the clearest cut of these is a parvenu who dons a bespoke blazer bought on credit, that is until that credit catches up with them. As a way to both dialectically, and emotionally resolve these representational paradoxes, Adolf Loos turned to the image of a formal dinner jacket, one which presents a standardized outward style to the world, while the interior lining could be decorated with whatever materials or embellishments the wearer wished to lavish on and for themselves. To Loos, this moral duality could be extended to urbanism as rows of homogenized planar white facades would likewise lend anonymity, and more importantly a freedom from others expression, in public space, while domestic interiors could be as individualized as each resident wished, respectively. Egalitarian (or kinky) as this may seem, Loos’ worldview presupposes that the psyche itself can be objectified so that here ‘white’ always signifies neutrality—an idea that today would be rightly decried as utterly Eurocentric.

Whatever his house might have looked like, Einstein allegedly went out of it oneday wearing two different colored socks. When queried why he did as such, he replied ‘I go by thickness, not color’. Hidden within this parable though is not a question of whose view is correct, instead it begs the question: whose window are you looking through?

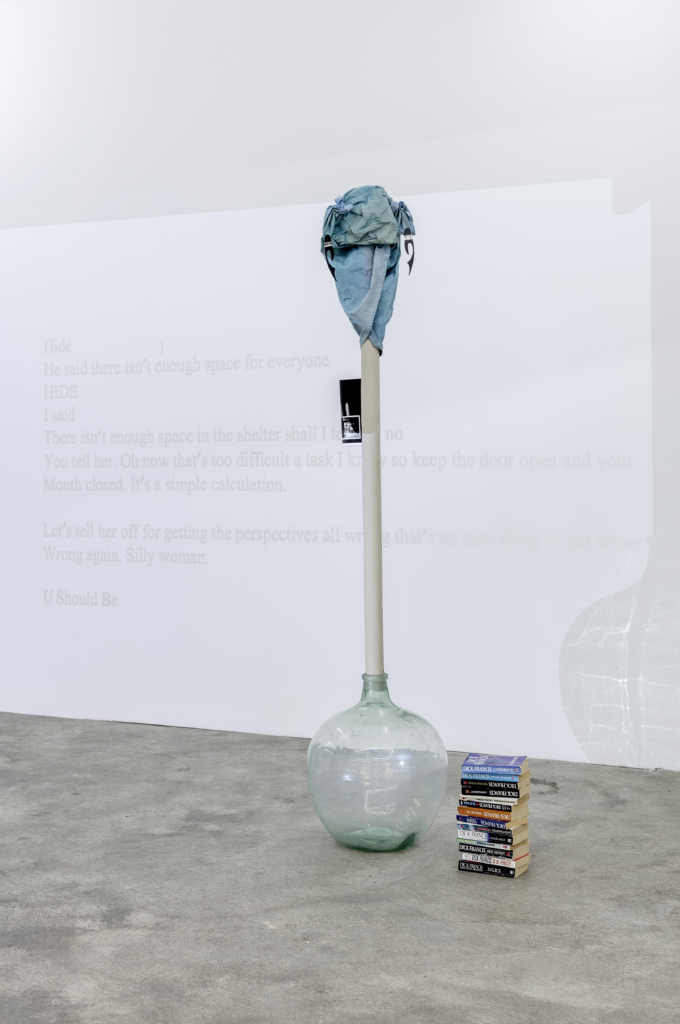

Procedurally, the works on view before you follow a straightforward methodology, give or take. It begins as the artist scours the streets of a given city, or digs through various repositories to unearth detritus, fragments, or other scrapped things. Many of these objects were mass-produced (read standardized), be they the door of an airplane, a clothes hanger, a stuffed animal or the like. Regardless of their original intention, they were estranged from it. In lieu of forensics, Jung intuitively recombines said objects, and likewise collages them into the totems now before you. At their feet lay diagrams that beguilingly tease you as they parody architectural plans. Just as a general may movie little figures around on a map, each is a speculation, generating another set of moves, which here ultimately lead to a set of associative poems spurred by the forms and logics of each set-piece. Another way to look at this however is to say that they are provocations. Do you ride a bike? If you do, I’m sure you just jump on it and go, and put little thought into the manner of riding itself. In fact, the process is so habituated that the expression ‘like riding a bike’ means a skill that once learned is never forgotten. Instead of thinking about how you don’t really think about how to ride a bike when you ride one, try to remember what it was like to first learn; were you wobbly, did you fall, were you more aware of balance, etc., than you are generally, what did you learn? As with all things, once we master them, or see them everyday, they become banal, taken for granted, and even cliché. Socially this phenomenon of acceptance is known as the status quo. Though the maintaining of relations does have countless merits, when social structures ossify around inequity, for just one many examples, new and lateral forms of thinking are required to creatively break through these formations, and articulate new patterns and ways of being. When I look at Jung’s practice, what I see is not what something looks like in the end, but instead I try to find the ways in which the images are spliced. In so doing, I learn how to look again.

Adam Kleinman

PRESS