Enchanted Restitution: Jala Wahid’s Metaphysical Reunification

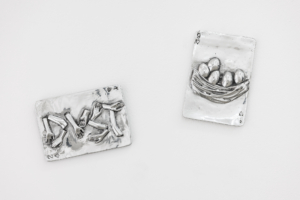

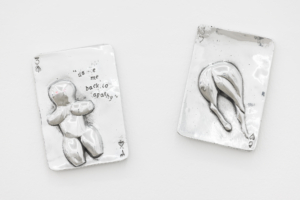

54 aluminium playing card sculptures, a series of monumental artefacts, evoke centuries of Western archaeological theft and imperial violence. Each hand-sized object is a testimony to past and ongoing colonial looting and cultural destruction, but also conjures a symbolic metaphysical reunification: assembling fragments of real and imagined ancient Mesopotamian material culture, either still buried and yet to be unearthed or plundered by North Americans and Europeans as part of a process of waging war in the Middle East. Jala Wahid’s Metaphysical Reunification (2023), critically engages with the Western museum collections that continue to hold items either outright stolen or taken under profoundly unequal structures of power. The project challenges racist justifications for Western imperialism and its fragmentation of Middle Eastern cultural heritage, and also speculates on what it might mean to picture the possibilities of restitution. The violence at the centre of the exhibition is both historic and contemporary: the work began as a response to a set of playing cards the US Department of Defence (DoD) issued in 2007 to its soldiers occupying Afghanistan (from 2001-2021) and Iraq (between 2003-11).

Games experiment with chance through sets of cultural rules: a medium used for entertainment, the DoD cards echoed a deck created by the US Army in 2003 that depicted Iraqi regime officials wanted for kill or capture. The 2007 version portrayed archaeological sites in Afghanistan and Iraq with pleas for their protection, alongside warnings against their intentional or wanton destruction and the trafficking of stolen artefacts. As a result of the invasion, the Iraq Museum was looted on a staggering scale in 2003.1 Visiting Babylon city’s ancient remains in 2005, British Museum curator John Curtis was shocked: troops had substantially damaged and severely contaminated the site by using it as a military depot.2 The DoD cards subsequently attempted to position US soldiers as custodians of Middle Eastern heritage, claiming it under Western stewardship as ‘part of our collective cultural history’ or significant for its Biblical associations.3 But despite Curtis’ horror, 21st-century imperialist destruction was the latest in a long line running directly back to his institution. Collector and politician Austen Henry Layard, who also worked for the UK Foreign Office and advocated for British control of the region, excavated Assyrian ruins from 1845 as a cover for spying, shipping the finds to the British Museum.4

Writing about a different continent, theorist Achille Mbembe’s decolonial philosophy is helpful to consider here. For Mbembe, European colonialism not only physically fractured sacred African objects through theft but also wrenched such material culture from its spiritual and social contexts, doing untold damage.5 These objects represented enormous symbolic deposits, ‘part of participatory ecosystems in which the world was not an object to be conquered, but a reserve of potentials’ as ‘vehicles of energy and movement … mediators between humans and vital powers’.6 Such a loss cannot be remedied solely by financial compensation, Mbembe argues, because it affected the capacity to bring about worlds – any restitution requires reparation by accounting for the profound harm enacted.7 In the context of the Middle East, Metaphysical Reunification symbolically brings together ancient Mesopotamian archaeological remains to attend to both colonial destruction and generate new imaginative worlds. While such re-enchantment cannot completely counteract the damage done, it can make claims for restitution while also speculatively re-animating certain cultural forms with a kind of supernatural power.

Western colonialism sought not just to capture and exploit the Middle East’s environmental and economic resources, but also shatter and steal its cultural and spiritual heritage in an attempt to break kinship networks, collective knowledge, and support systems. After acquiring the spoils, US and European archaeologists or museums laundered racist ideas.8 In such a context, time as a concept was co-opted into linear narratives of imperial progress, despite being contested by anti-colonial traditions of thinking about temporality in other ways.9 As though the past and present cascade against each other, Wahid’s sculptures symbolically connect a series of artefacts crafted between 4000-330 BCE across an area later carved up with 20th century borders by Western powers. Items include a sculpted gold ibex, painted terracotta human statuette, clay human figurines, stamp seal, broken rock bull ear, duck-shaped measuring weight, clay animal toy, marble fragment with plant and scorpion design, fired clay rattle, gold cockle-shell shaped container, inscribed agate eye stone – currently held by the British Museum, Louvre Museum, Met Museum, Chicago University, Morgan Museum and Library. Many relate to the natural world or human bodies, for use in rituals or everyday life. Wahid found an enduring relevance for these objects, once used to protect against miscarriage or death, able to speak across time.10

Concerns about the natural world, for example, are both perpetual and specific to the fossil fuel extraction that drives recent Western military intervention – part of a much longer European project to persecute paganism and enclosure nature.11 Despite such destruction, encountering objects in the British Museum was a transformative experience for Wahid: she found that they embodied the emotional charge of those who crafted them, their ‘material quality held immaterial forces’.12 Wahid’s practice could be described as re-vitalisation: investing the fragments with energy or potential once stripped by forced relocation and the British Museum’s imperative to catalogue the world by rendering it inert through an Enlightenment framework. The artist explained that the project ‘was an instance where I could begin to contend with the metaphysical qualities of these ancient objects’.13 She pictures them unified across space and time, using fiction to address archival gaps or missing and buried heritage.14 Wahid symbolically re-assembles the artefacts together to protest their loss and invest them with a vital force. The sculptural series appears enchanted with very old forms of magic, mediating humans and the divine, drawing on ancient aesthetics to animate their profoundly affective power in the present.

Edwin Coomasaru

1 Craig Barker, ‘Fifteen years after looting, thousands of artefacts are still missing from Iraq’s national museum’, The Conversation, 9 April 2018, https://theconversation.com/fifteen-years-after-looting-thousands-of-artefacts-are-still-missing-from-iraqs-national-museum-93949, accessed 19 April 2023.

2 Rory McCarthy and Maev Kennedy, ‘Babylon wrecked by war’, The Guardian, 15 January 2005, https:// www.theguardian.com/world/2005/jan/15/iraq.arts1, accessed 19 April 2023.

3 Shawn Malley, ‘Layard Enterprise: Victorian Archeology and Informal Imperialism in Mesopotamia’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 40, No. 4 (2008), pp.623-646, p.624, p.626.

4 Malley, p.632-635, p.637-641.

5Achille Mbembe, Out of the Dark Night: Essays on Decolonization (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2021), p.159-171.

6 Mbembe, p.163, p.166, p.169.

7 Mbembbe, p.170-171.

8 See, for example: Debbie Challis, The Archaeology of Race: The Eugenic Ideas of Francis Galton and Flinders Petrie (London: Bloomsbury, 2013)

9 Priya Satia, Time’s Monster: History, Conscience and Britain’s Empire (London: Allen Lane, 2020), p.3, p.43.

10 Jala Wahid and Theresa Roessler, ‘Interview with Jala Wahid’, in Theresa Roessler ed., Mock Kings (Freiburg: Kunstverein Freiburg, 2023), pp.3-14, p.11.

11 James Marriot and Terry Macalister, Crude Britannia: How Oil Shaped a Nation (London: Pluto Press, 2021), p.136, p.188-189; Jason Hickel, Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World (London: Windmill Books, 2020), p.63-78.

12 Wahid and Roessler, p.13.

13 Wahid and Roessler, p.13.

14 Wahid and Roessler, p.2, p.13.

PRESS