M + E = ME. “ME” stands for Marriage Encounter – “marriage care” in the Catholic sense. “ME?” asks the eccentric being who catches sight of themselves in the mirror of the other, learning to see themselves through the other’s eyes. “ME!” mechanizes Taylor Swift into a corporate jingle, piping fresh frosting on vintage empowerment: self-love as an airtight plastic wrapping. “M.E.” is the true relic of the artist’s ego, the spun paraphrase of God that doesn’t take itself too seriously and busts the bluff after all.

ME-NA-CE is the threat that can be both threatening and threatened. Consider the erstwhile slur “Lavender Menace”: originally coined in 1969 by activist and writer Betty Friedan to capture the perceived danger that open lesbians posed to the nascent women’s movement, those lesbian feminists turned the affront into a t-shirt slogan against their own exclusion. It didn’t take long for journalist Susan Brownmiller to trivialize the “lavender menace” movement again in a New York Times article: it is not about a threat, but a “red herring” – an empty threat?

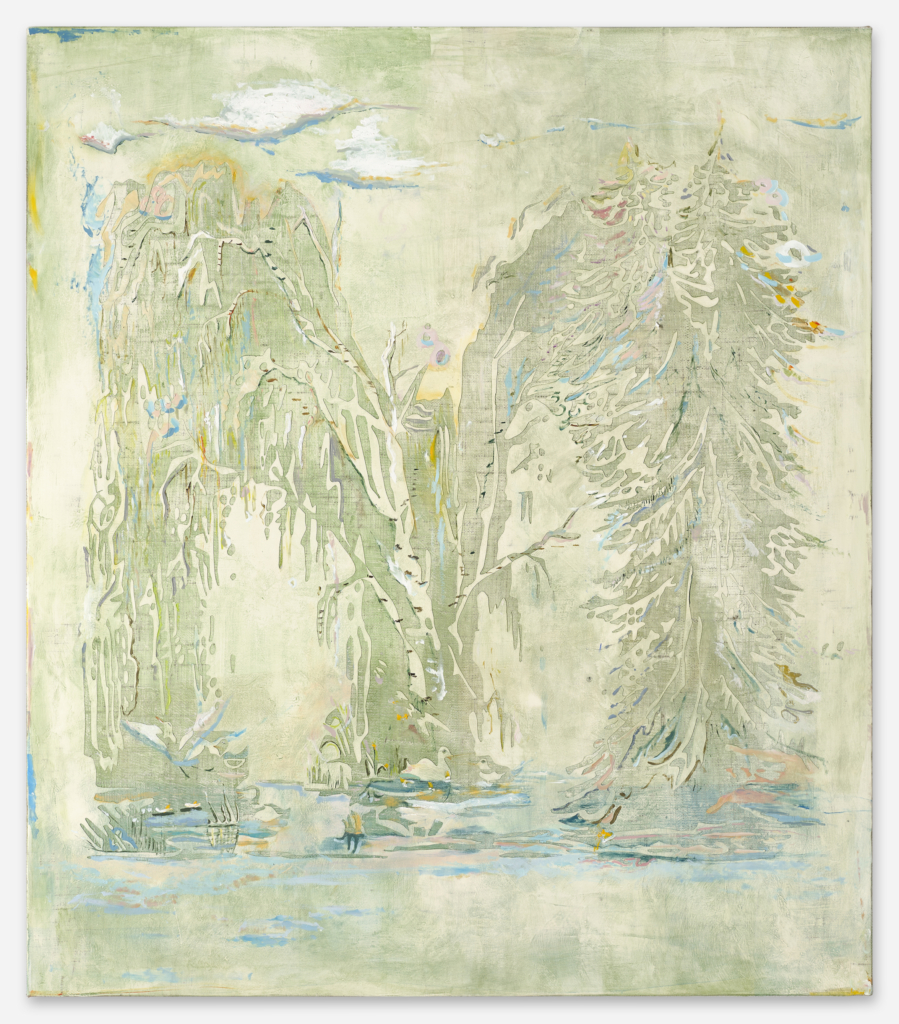

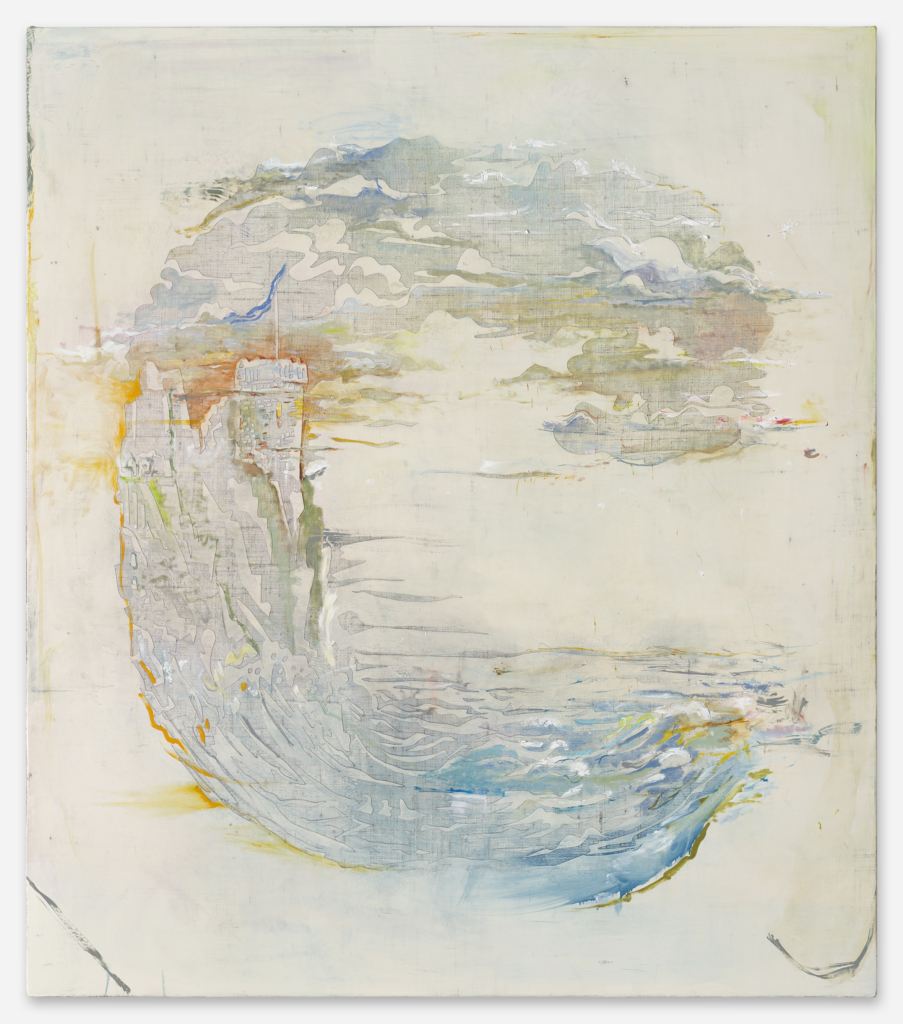

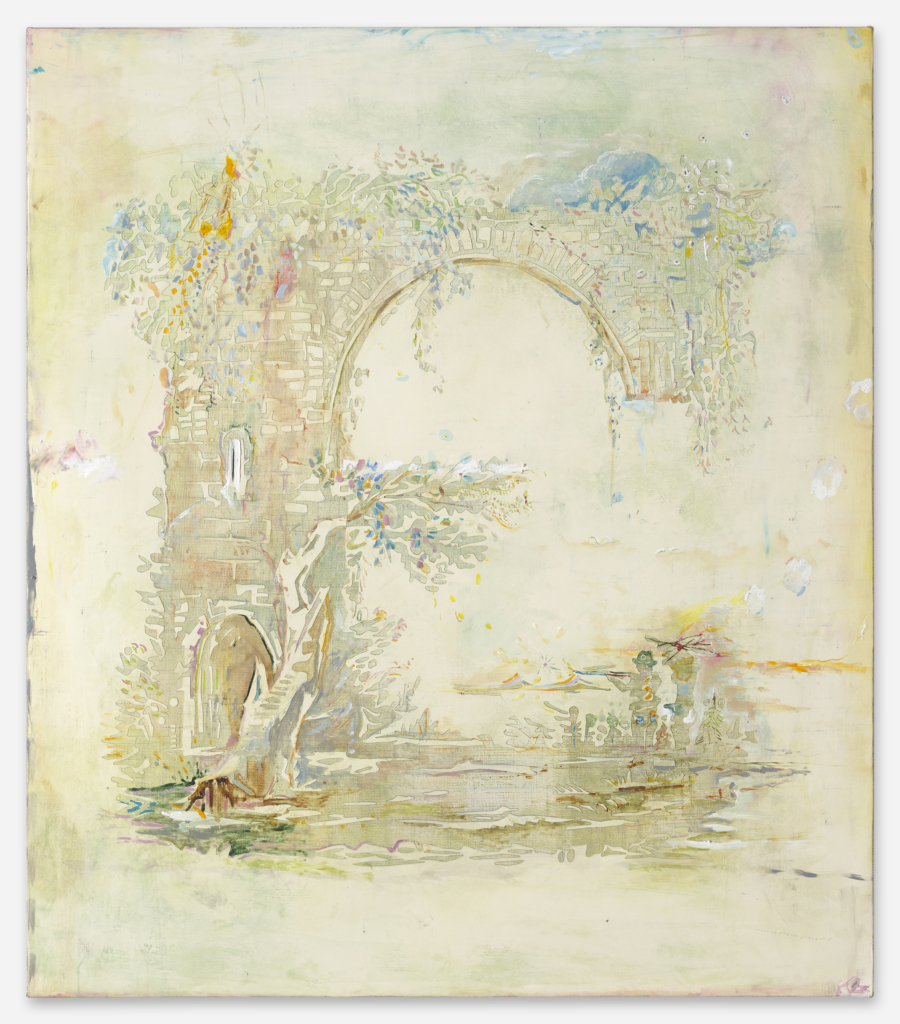

“ME-NA-CE” is the visual threat in images that shakes its own potency. Staggering between typography and iconic motif, initials formed from figures from ancient masonry arch, and quaint arboreal arabesques melting into pools of ponds and clouds somehow lull viewers into safety with colourful pathos on canvas. They affirm, whisper, even propagate, as if immortalized in gravestones, yet never quite uttering truisms of old-fashioned Grimm fairytale virtue ideology.

Despite initial reservations about the atrocious fairy tales, these folksy stories were also intended to enable children in the GDR’s “Friedensstaat,” (“anti-fascist peace state”) to be morally consolidated and “boldly dream into the future” around the cosy collective campfire: whether with the help of today’s long running Christmas eve tale Three Hazelnuts for Cinderella (1973) or, for example, The Cold Heart (1950) by Wilhelm Hauff, which was revived by DEFA (the state-owned film studio) as the first fairy tale adaptation in colour, in which “Kohlenmunk-Peter” (“Coal-marmot Peter”) trades his heart for a stone and the curse of money.

The power of inflated homesickness for the past, to the retrograde alternate reality, triumphs when it passes over into everydayness. So, too, in the case of an exhausted letter painting in the gallery, when it threatens to lose its “aesthetic fascination.” Just as quickly as the iconographic letters on the walls initially threaten to be paranoidized into reckless acronyms, legible meaningfulness, at second glance their backbone threatens to break again. A naked silhouette character in a slip with painted-on orange nipples, a green ribbon on a Beuys hat, and a brandished pistol literally threatens the histographic self-assurance of the “E” letter and (in the same image) is prodded in the back by a gun under a sweater – or – an erect penis. Almost as if it were a semi conscious image within an image, a semi-conscious story within a story, a semi-conscious film within a film (one thinks, for example, of Agnes Varda’s Lions Love, 1969).

Appearances deceive the simple-minded in this farce, where a gloating boxing punch sometimes slips painfully below the belt to decipher, dismantle, complicate what preserves, reduces, or threatens to massage itself back into our cortex as the emperor’s new clothes, as the one true visible entity. In contrast, the images hanging here virtually flicker during their “phantomization”, exposing themselves only to withdraw again in the next moment.

So, too, a forgotten colour bomb after the explosion in the freezer: an image in which seeing is not only “seeing something” and seeing “into something,” but at the same time a being looked at beyond Panofsky’s demands for identification; one in which the gaze of the other becomes that of the image and in turn eyeballs us. The images that we once created are thus ultimately able to stop us cold. The diagnosis is: “split in seeing” or as Didi-Huberman would say: “Ce qui nous regarde” (“What we see looks back at us.”) The twofold visibility of the image dazzles, seizes us and yet keeps aloof – like an open, lightflooded portal in front of which a bouncer lures us again and again with the same threat: “Komm’ Se rin, könn’ Se rauskieken!” (“If you come in, you can look out!”) and yet, unimpressed by pitiful attempts at false advertising, mercilessly denies entry.

What is left to do? Possibly a provocative change of view as a doubtful action, in which the most multifaceted bodily fluid plays the lead role against the imperative. Because humour is known as laughing in spite of it all. And who laughs nevertheless – namely from below, exactly at forbidden localities, in the “piss corners” of ideologically larded dilemmas of the higher-order, remaining superior in all imperfection – and in fact non-cowardly. As Da Vinci once said: “Threats alone are the weapons of the threatened man.”

Elisa R. Linn