In the ongoing series After Hours, Sophie Thun uses her body again as a tool to examine and question established concepts. The artist photographs herself in various hotel rooms, which she occupies while doing production work for (mostly male) colleagues realizing their own projects. In doing so, she draws attention to a circumstance that is rarely mentioned in discussions on contemporary art: many established artists have their work produced by workshops and various assistants or specialists, either in part or entirely. These workers are often artists themselves who are dependent on additional jobs to support their own artistic practices. Dependency relations like these consolidate hierarchical structures, not least because at the end of the day they determine who can literally afford to dedicate more time to their own artistic work.

The hotel also represents a venue for erotic fantasies, a place where lovers meet to indulge in their passions and to live out affairs. Here, Thun points to a gender-specific phenomenon: it is almost exclusively women (especially in the art world) who are faced with the deeply derogatory and heteronormative accusation of “sleeping their way to the top” and such a location lends itself to scenes of imagination. Thun fuels this idea by capturing herself naked and in explicitly sexual poses, either with a shutter release cable in her hand or in front of a mirror. She never seems to be alone. Analogue montage techniques allow her to create the illusion that she is interacting with herself, pleasing herself. In the hotel room, paid for by a third party, this masturbatory act represents a reclaim of control over one’s own body.

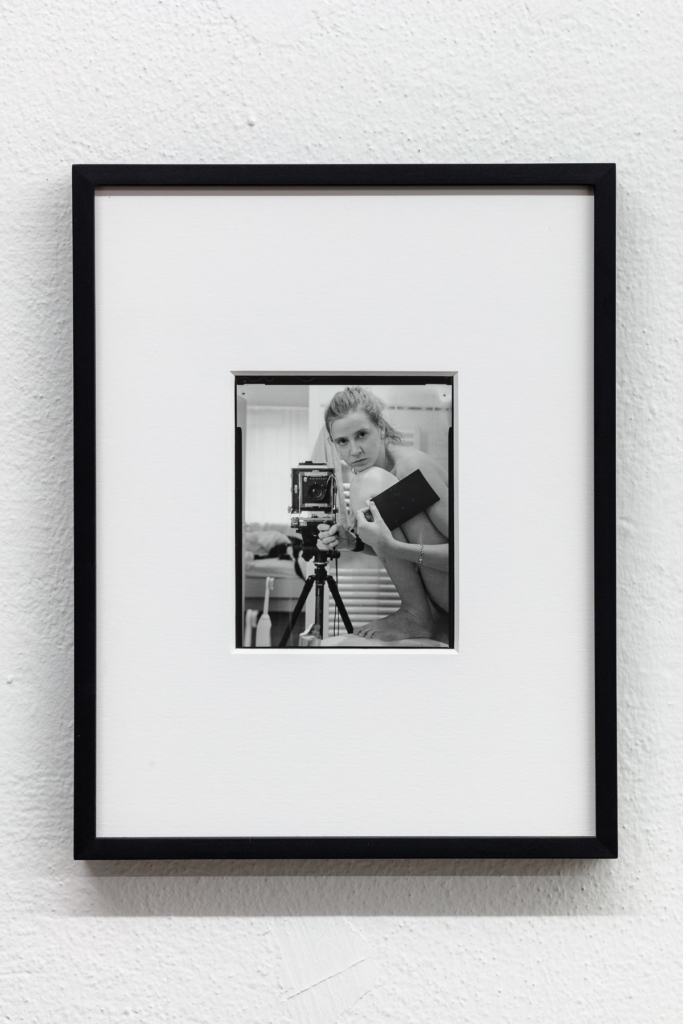

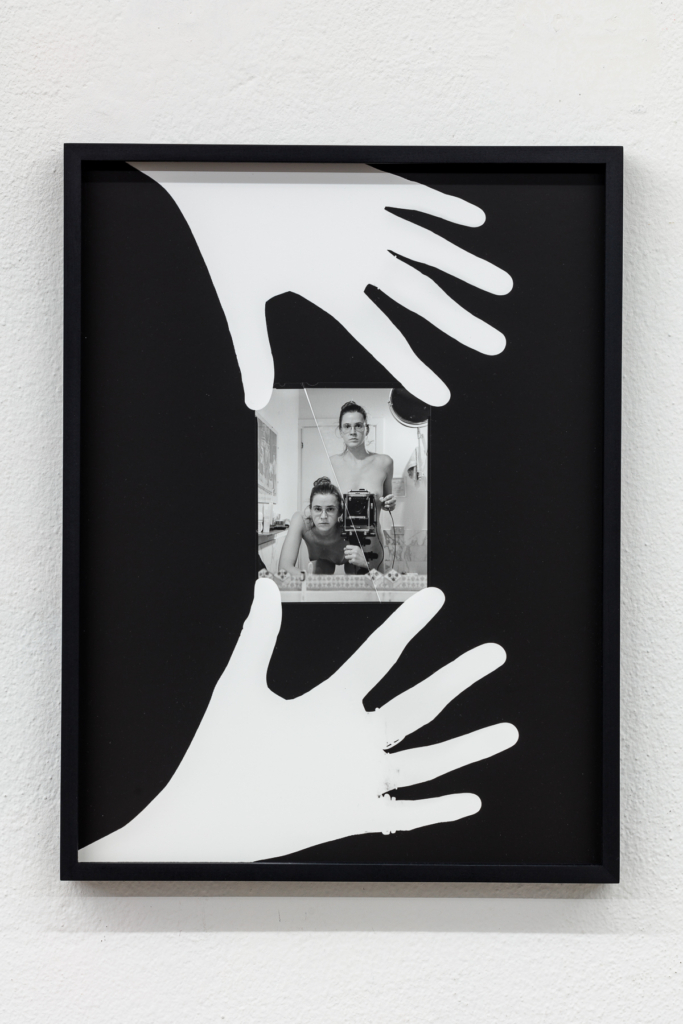

Thun’s self-portraiture is only a means to an end. Her self-representation is not entirely a characterizing portrait in the art historical sense, which interfaces between self-staging and a curious self-observation. Instead, the artist consistently encounters her audience with a steady and rigid gaze that is as alienating as it is challenging. The appeal is to our thoughtless consumption of photographs, a medium whose manipulative possibilities are still shrouded in dense veils, especially with regard to the depiction of women. In contrast, Thun emphasizes the presence of the camera. She exposes the photographic process by exposing the entire negative as a contact print and exposing the parts where it has been cut. Around it, the outlines of her hands – characteristic white spaces that appear when Thun holds the negative on photo-sensitive paper and shines light on it – clearly indicate the artist’s authorship. Like a common thread, the deconstruction of the medium runs through the artist’s young oeuvre, enabling her to repeatedly address new questions.

Magdalena Vuković