To set free, set forth, let go, unleash; to excuse, deliver, and absolve; to make public, issue, announce, declare, report, reveal, publish; to communicate, disseminate, and launch; to release.

Revolving around the construction of self in the conflicted space of representation, the multi-layered photographic interventions by Vienna-based artist Sophie Thun (* 1985) complicate the relationship between the imaginary pictorial space of the image and the real space of the viewer. By revealing the sites, mechanisms, and performances inherent in the production of the image, Thun breaks its seamless illusion, honestly documenting the performance of its construction. Images, like self-representations, are not objective representations of reality, but tricky, superimposed, staged processes, that develop over time. In the exhibition Double Release, Thun presents new, mostly site-specific works that invite the viewer to question notions of (representational) space and our ways of seeing.

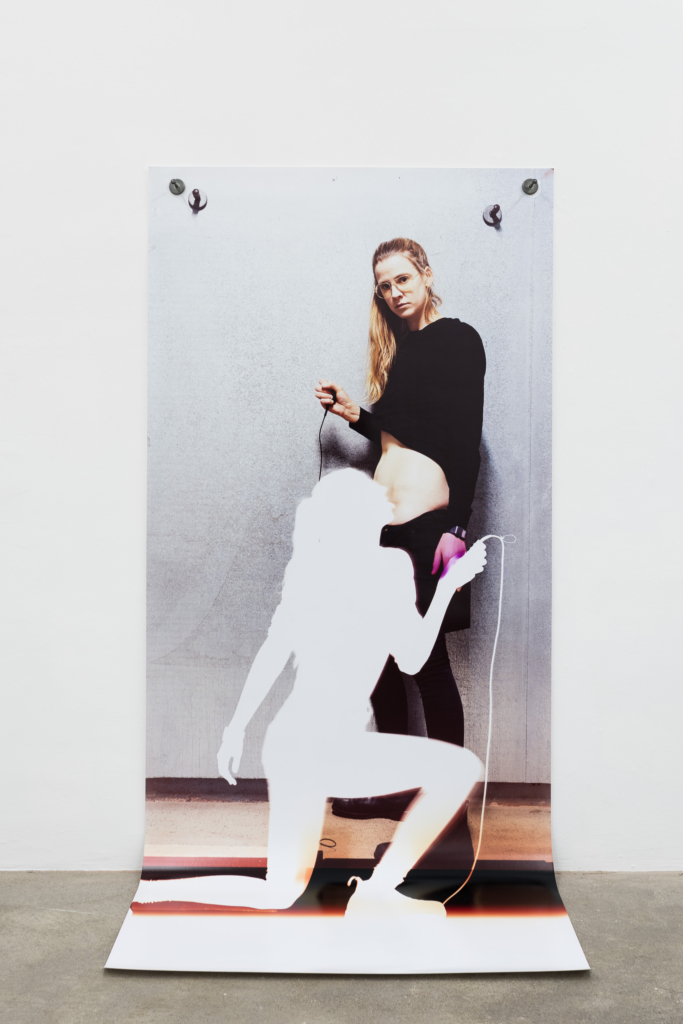

One of the two largest works in the gallery While holding (passage closed) (2018) is made up of six panels of slightly overlapping photo paper, covering the gallery wall from ceiling to floor. The work, produced on-site and in the darkroom, depicts a life-size image of the artist in the gallery space taking her own picture, while holding up an existing photographic print in which she is again portrayed in the act of taking her picture. In both the physical work and the mise-en-abyme, Thun is dressed in all black, her stance is firm and wide, and she faces the viewer head on. In her right hand, Thun grasps the camera’s cable release, the apparatus’ extension, permitting her to inhabit the role of artist and other, producer and performer. A prothesis of sorts, the cable release connects Thun to the apparatus necessary to capture her image.

In While holding (passage closed) we also see two imprints of the artist’s body – photograms – produced in the darkroom, the second and otherwise invisible site of (re)production. Using a horizontal enlarger on tracks to project the 8 x 10” negative taken on-site in the gallery, Thun presses her body up against the undeveloped paper for the duration of exposure, blocking the light from hitting the emulsion on the surface. The presence of the artist’s body creates an absence in the image, an absence relating to the incapability of capturing the human body on a two-dimensional surface. Even in this most direct transfer possible, the imprint or photogram fails to represent the living, breathing, and feeling body. Or rather, the body itself evades representation. Only a mark remains.

Pointing the camera at herself, Thun draws awareness to the camera’s violence, a “sublimation of the gun” as Susan Sonntag once wrote, and to the violence of the male gaze perpetuated by it. As Laura Mulvey tellingly explains in her seminal work “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” the “active male gaze projects its fantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.”(1) Pleasure is thereby defined for and by an active male viewer, the object of desire is passive and at his disposal. Female self-representation is consequently an act of emancipation and resistance, a simultaneous appropriation and undermining of the male gaze, the dominant way of seeing.

There is a long tradition of female self-representation in European art history, unearthed and reclaimed in the feminist inquiries in the second half of the 20th century. Some of the earliest examples date back to the Renaissance: painters such as Sofonisba Anguissola, Artimisia Gentileschi, Clara Peeters, or Judith Leyster addressed the roles they where given as female artists in their self-portraits. Comparing, for example, the Self-portrait at the Easel (1556) by Sofonisba Anguissola with Thun’s While holding (passage closed), there is a striking similarity. Both artists depict themselves while working, referencing their profession by revealing the tools of their craft, and their virtuosity by the use of mise-en-abyme. Both artists look out at the viewer from the two-dimensional space of representation.

In addition to her decisive acts of self-representation, Thun utilizes effects of trompe-l’oeil, another method employed since the Renaissance to heighten the viewers awareness of a staged reality. Defined as a painted representation so real the viewer mistakes it for the actual object, trompe-l’oeil is able to subvert Cartesian perspective through excessive mimesis, drawing attention to the artifice of the two-dimensional space of representation. By up-scaling her photographic interventions to mimic the exact dimensions of the gallery and by employing the formal technique of the mise-en-abyme, Thun challenges our culturally and historically constructed ways of seeing.

Images, we can conclude, do not represent the world as it is but assemble a world as we imagine it to be. For the last two thousand years, a male perspective has predominantly defined this assemblage. Taking matters into her own hands, Thun produces her own image, yet, at the same time, releases us from the illusion of its wholeness. Above all, Thun exposes the limitations of sight and representation through the absences in her photographic works. The archive of gestures and movements during (re)production, the bodies that touch, feel, and desire can never be fully captured in the image. That is why she took my hand led me into the darkroom. Her hand directed mine over every surface, crevice, and button, allowing me to become a part of her process, a process of double release.

Lisa Long

(1) Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. Eds. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen.

New York: Oxford UP, 1999: 837.